Chronic kidney disease (CKD) represents a silent epidemic that grows with aging populations, rising rates of diabetes and hypertension, and widening disparities in access to care. In many regions, a substantial portion of individuals with CKD remain unaware of their condition until kidney function has already declined substantially. The consequences are not only personal—rising risk of cardiovascular events, progression to end-stage kidney disease, and increased dependence on dialysis—but also societal, in the form of higher healthcare costs and strain on families and caregivers. Against this backdrop, artificial intelligence emerges as a powerful ally capable of synthesizing disparate signals from laboratory tests, imaging studies, wearable sensors, and longitudinal clinical records. The promise of AI in early detection rests on three pillars: speed, to triage patients who require attention promptly; breadth, to discover patterns that elude human analysis when data are multi-modal and longitudinal; and scalability, so that screening and monitoring can extend beyond specialist clinics to primary care and community settings. Early identification of CKD offers a window to intervene with lifestyle modifications, medical therapy, and careful management of comorbid risks that can slow progression and improve outcomes.

CKD often begins long before symptoms appear, with subtle changes in kidney function that may be obscured by natural variability in laboratory measurements or by competing health priorities. The classic markers, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and albuminuria, provide snapshots of current kidney status but may miss progressive trajectories that unfold over months or years. An individual might experience brief dips in eGFR or transient elevations in creatinine that normalize, yet the underlying disease process continues. Heterogeneity in etiologies—from hypertensive nephrosclerosis to diabetic nephropathy to glomerulonephritides—means that a one-size-fits-all screening interval often fails to catch early decline in some patients while over-screening others. The challenge, therefore, is not merely to detect abnormal values but to recognize meaningful trends, interactions with age, race, sex, and comorbidities, and to forecast who is most at risk for rapid progression. AI offers a framework to learn these patterns from large, diverse datasets and to translate them into actionable risk signals for clinicians and patients alike.

Traditional screening relies on periodic testing and rule-based risk calculators that aggregate a handful of variables into a risk score. While these tools have improved screening in many settings, they tend to be static, infrequent, and limited in their ability to integrate dynamic data streams such as daily blood pressure readings, urine albumin fluctuations, or evolving imaging features. Artificial intelligence reframes this problem by continuously ingesting multi-source data and updating risk predictions as new information arrives. In practice, AI can support clinicians by highlighting patients whose trajectory appears unfavorable, prompting timely investigations or therapeutic adjustments. It can also illuminate subgroups where conventional models underperform, such as individuals with atypical presentations or those whose risk is shaped by complex social determinants of health. Importantly, AI does not replace clinical judgment; it acts as a decision-support companion that amplifies the clinician’s capacity to detect early CKD and to intervene before irreversible damage occurs.

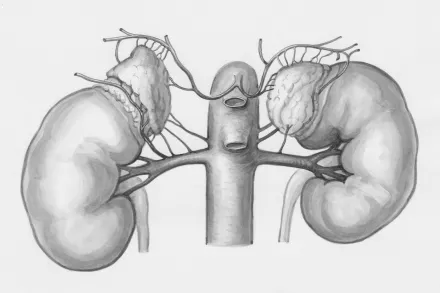

Effective AI systems for early CKD detection rest on the availability of high-quality, diverse data. Electronic health records provide longitudinal lab results, vital signs, medication histories, and diagnostic codes that reveal trajectories over months and years. Laboratory information systems deliver precise measurements of eGFR, creatinine, albuminuria, electrolytes, and metabolic markers, while imaging databases furnish ultrasound, magnetic resonance, and sometimes computed tomography data that encode structural and functional information about the kidneys. In addition, burgeoning fields such as proteomics and metabolomics contribute novel biomarkers that reflect pathophysiological processes long before overt dysfunction becomes apparent. Wearable devices and at-home testing technologies generate continuous or near-continuous streams of data, including blood pressure patterns, hydration status, and activity levels, which may interact with kidney function in complex ways. The integration of these sources is not trivial; it requires careful attention to data quality, harmonization of measurement units, handling of missing values, and robust privacy safeguards to gain patient trust and regulatory approval.

Among the machine learning approaches applied to early CKD detection, supervised learning algorithms such as gradient boosting, random forests, and neural networks are trained to predict outcomes based on labeled examples, for instance future decline in eGFR or progression to end-stage disease over a defined horizon. Time-to-event modeling, including extensions of Cox proportional hazards models and recurrent neural networks, enables the incorporation of time-varying covariates to capture risk progression. Deep learning methods, particularly convolutional networks and their variants, are employed to extract informative features from imaging data and to process waveform signals, while attention mechanisms help identify which data points most influence predictions. Explainability techniques, including model-attribution methods and interpretable architectures, are increasingly used to reveal the rationale behind risk signals, which is essential for clinician acceptance and patient communication. Across projects, external validation on representative cohorts remains a non-negotiable step to ensure that models generalize across diverse populations and healthcare settings.

AI-powered biomarker discovery in kidney disease blends conventional measures with novel candidates derived from omics data, urine proteomics, and metabolite profiles. These signals may reflect glomerular integrity, tubular injury, inflammatory states, or hemodynamic stress, and they can be tracked over time to reveal early deterioration before eGFR falls. Imaging, too, benefits from AI, as machine vision techniques quantify subtle texture changes in ultrasound images or detect patterns in MRI scans that correlate with early nephron damage or fibrosis. For example, radiomic features extracted from abdominal ultrasound or renal MRI can serve as early surrogates for histopathological processes, enabling noninvasive risk stratification. When AI systems fuse biomarker trajectories with imaging cues and clinical histories, they produce composite risk profiles that more accurately identify individuals who are likely to experience clinically meaningful decline, guiding timely interventions such as optimized blood pressure control, renoprotective medications, and lifestyle modifications that reduce cumulative kidney injury over time.

Wearable and home-based monitoring technologies extend the temporal horizon of kidney health assessment beyond sporadic clinic visits. Continuous blood pressure monitoring, circadian rhythm analysis, and dehydration surveillance provide context for understanding fluctuations in kidney function that might otherwise be misattributed to random variation. In people with diabetes, hypertension, or evolving CKD risk, sensor data can reveal patterns of nocturnal hypertension, postural changes, or salt-water balance that contribute to renal stress. Smart scales, activity trackers, and patient-reported outcomes enrich data streams with behavioral and functional dimensions that influence the progression of kidney disease. AI can synthesize these signals with laboratory values to produce personalized risk trajectories, enabling early counseling and proactive management. The practical challenge lies in ensuring data quality, aligning patient participation with clinical workflows, and maintaining privacy while delivering meaningful, timely feedback to patients and clinicians alike.

Before AI tools can change practice, they require rigorous validation across populations and settings that differ in demographics, disease burden, and care delivery models. Prospective studies and pragmatic trials help determine whether AI-assisted screening translates into earlier interventions, slower eGFR decline, and fewer dialysis starts without increasing harm from false positives or alarm fatigue. Regulators evaluate performance metrics such as discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility, and they scrutinize transparency, data governance, and post-market monitoring plans. Clinicians must see that AI recommendations align with established clinical guidelines and that the tools can be integrated into existing electronic health record environments without adding operational burden. Building user trust also depends on clear explanations of how predictions are generated and on the ability to audit models for bias or drift over time. When validated and properly deployed, AI can augment the clinician’s judgment, streamline workflows, and help allocate limited resources toward patients most likely to benefit from early nephroprotection.

AI in kidney health care raises important ethical questions about equity, privacy, and accountability. If datasets underrepresent certain populations—for example, rural communities, racial minorities, or individuals with limited access to care—models may fail to detect risk in those groups, exacerbating disparities rather than closing them. Privacy protections, informed consent for data use, and transparent data stewardship are essential to maintain patient trust in AI-enabled screening programs. Clinicians must balance the benefits of early detection with the risk of false alarms that could cause undue anxiety or lead to unnecessary testing. The design of alert systems should minimize interruptive noise and provide context so that clinicians can interpret risk signals within the broader clinical picture. Finally, responsibility for decisions that follow AI recommendations must remain shared among the patient, the clinician, and the health system, ensuring that human oversight remains central even as machines assist in pattern recognition and forecasting.

Translating AI from research to routine care requires thoughtful integration into clinical workflows, interoperability with health information technology, and continued education for healthcare teams. Effective deployment starts with data governance: ensuring data quality, standardization, and robust privacy safeguards; moving toward federated learning models that train across institutions without sharing raw data can help preserve privacy while improving generalizability. User-friendly interfaces and clinician-facing dashboards are essential, presenting risk trajectories, key drivers, and recommended actions in an interpretable and actionable format. Integration with decision support systems must respect clinical autonomy, offering options rather than mandates. Reimbursement considerations, workflow time, and the availability of nephrology specialists influence adoption, as do patient acceptability and digital literacy. In settings with limited resources, AI-based screening can enable targeted outreach and community-based programs that identify high-risk individuals who otherwise would not be screened, creating opportunities for early nephroprotection at a population level.

The frontier of AI in early CKD detection is defined by models that can learn from diverse, real-world data while protecting patient privacy. Advances in federated and privacy-preserving learning enable multi-institution collaborations without raw data sharing, increasing representativeness and reducing bias. Integrating multi-omics data with imaging and clinical histories promises to reveal mechanistic pathways and identify individuals who will respond to specific interventions. Preference for model interpretability is unlikely to wane, driving the development of transparent architectures and user-centered explanations that clinicians can trust. Real-world evidence generation will expand beyond controlled research environments into community clinics and population health programs, producing insights about implementation, acceptability, and long-term outcomes. As AI-driven detection thresholds become more nuanced and personalized, clinicians will tune screening intensity to individual risk profiles, potentially shifting the goal from universal screening to precision screening that allocates resources efficiently while maintaining safety and equity.

For healthcare systems, a practical roadmap begins with a clear articulation of aims, governance structures, and oversight for AI-enabled screening programs. Data interfaces must be standardized, and privacy controls reinforced, with a plan for ongoing model validation and calibration across diverse patient groups. Clinicians should participate in co-design efforts to ensure tools fit into daily practice, with education that covers interpretation, limitations, and actionability. Patients benefit from transparent communication about how AI contributes to care, what data are used, and what outcomes to expect, including how early signals translate into preventive strategies. Health systems must consider equitable access, ensuring that AI tools do not widen disparities and that marginalized communities receive the same opportunities for early detection. Finally, researchers should pursue rigorous, reproducible studies that report both improvements in early detection metrics and real-world clinical outcomes, while sharing datasets and model artifacts in ways that respect privacy and foster collaboration across the nephrology community.