Stem cell research sits at the intersection of biology, medicine, and ethics, weaving together the science of cellular identity with the practical goals of healing and restoration. The field explores cells with the unique ability to divide and to differentiate into various specialized cell types, offering a lens into how tissues develop, repair, and sometimes fail. In medicine, this inquiry translates into potential therapies that aim to replace damaged tissues, restore function after injury, and treat diseases that have long remained stubborn to conventional approaches. The journey from basic cell biology to clinical applications involves a careful dance between laboratory discoveries, animal studies, regulatory oversight, and the lived experiences of patients seeking relief or cure. As researchers map how stem cells interpret signals from their surroundings, clinicians anticipate how to guide those signals in ways that are safe, effective, and ethically sound. The promise is broad, touching fields as diverse as neurology, cardiology, ophthalmology, orthopedics, and immunology, while the responsibilities accompanying that promise demand thoughtful governance, transparent communication, and ongoing risk assessment. This article delves into the science, the history, the methods, the medical applications, and the ethical and regulatory considerations surrounding stem cell research, all presented in a way that aims to illuminate rather than oversimplify the complexities involved.

To begin, it is helpful to clarify what is meant by a stem cell. At the core, a stem cell is a cell type endowed with two key properties: the capacity to self-renew, that is, to divide and produce more stem cells, and the ability to differentiate into one or more specialized cell types. This dual potential gives stem cells a central role in the development of organisms, in tissue maintenance, and in regeneration after injury. Not all stem cells are alike, however. Some reside in specific tissues and contribute to the natural turnover of certain organs, while others can be reprogrammed in the laboratory to assume new identities. The study of how stem cells decide what kind of cell to become is a window into developmental biology, revealing how genes, epigenetic marks, and environmental cues orchestrate the fate of a cell. When scientists harness this developmental plasticity in a controlled and safe manner, they gain a powerful means to model diseases, test therapies, and potentially repair damaged tissues in patients who have exhausted standard treatments. Yet the very features that make stem cells so promising also demand rigorous safeguards, because guiding a cell toward a particular fate can have unintended consequences if not done with precision and oversight. The ongoing work embodies a blend of curiosity, creativity, and caution, as researchers seek to translate laboratory insights into clinical benefit while maintaining the highest standards of patient safety and scientific integrity.

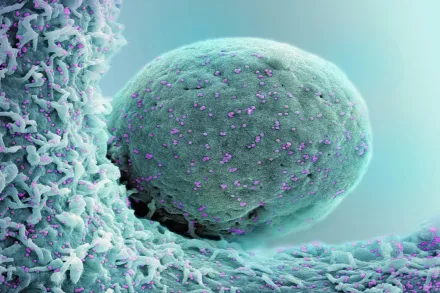

The field is driven by a spectrum of cell types, each with its own advantages for investigation and treatment. Embryonic stem cells, derived from early-stage embryos, once drew intense ethical debates because of their origin, yet they are noted for their remarkable versatility, with the potential to differentiate into almost any cell type in the body. Adult stem cells, found in various tissues such as bone marrow, skin, and the brain, exhibit a more limited differentiation repertoire but are often less controversial and closer to natural physiological conditions in the body. A powerful modern addition to the toolkit is induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs, which are ordinary adult cells cleverly reprogrammed back to a pluripotent state, essentially resetting their identity. The ability to create patient-specific iPSCs opens doors for personalized approaches to modeling disease, testing potential therapies, and, in some contexts, regenerating tissue without provoking an immune response. In practice, researchers may combine multiple cell types in a therapeutic strategy or use them to build models of disease in the laboratory, with the ultimate aim of informing safer and more effective clinical interventions. These distinctions matter because they influence the speed of translation from bench to bedside, the ethical considerations at stake, and the regulatory pathways that must be navigated before a therapy becomes available to patients. The field remains dynamic, with advances often opening new possibilities while also presenting fresh questions about safety, effectiveness, and equitable access for diverse populations.

The clinical promise of stem cell research is grounded in regenerative principles, the idea that damaged tissues can be repaired or replaced by cells that can restore structure and function. In many organs, such regeneration is limited or slow, leading to chronic disability, pain, or progressive decline. By introducing cells that can replace lost or dysfunctional elements, physicians hope to reverse disease processes or halt progression. Yet the practical realization of this promise requires more than simply delivering cells to a patient. It demands an understanding of how transplanted cells integrate with the host tissue, how they survive and differentiate in the new environment, how they communicate with resident cells, and how the immune system responds. The complexity of these interactions means that success is rarely achieved by a single technique. Instead, progress accrues through iterative cycles of discovery, optimization, and careful monitoring in clinical contexts. The overarching aim is not only to produce a momentary improvement but to create durable, functional restoration that improves quality of life without introducing new risks. The conversation around stem cell therapy thus encompasses scientific nuance as well as patient-centered considerations, ensuring that the pursuit of innovation remains aligned with real-world needs and ethical standards.

What are stem cells and why do they matter

Stem cells occupy a foundational role in biology because they hold the potential to generate the many specialized cell types that comprise tissues and organs. This capacity to give rise to diverse lineages makes them not only central to development but also to potential remedies for conditions in which tissue is lost or failing. Bodies maintain a repertoire of stem cells that support normal physiology, from the renewal of blood into new red and white cells to the continual replacement of skin and the repair of minor injuries. When disease or trauma disrupts the normal balance of tissue, stem cells become a focal point for strategies aimed at restoring function. In laboratory settings, scientists study how stem cells respond to growth factors, mechanical cues, and chemical signals that guide their choices. This research illuminates fundamental questions about how cells interpret information and how small changes in signaling pathways can lead to large differences in behavior. The practical upshot is a growing repertoire of approaches that can be tailored to different tissues, with the potential to replace or repair components that no longer function well, whether due to congenital issues, aging, or acquired diseases. As researchers map these pathways, they also learn about the safeguards necessary to ensure that encouraging one desirable outcome does not trigger unintended effects elsewhere in the body. This balance between possibility and prudence is a constant feature of stem cell science, shaping both experimental design and clinical trial planning.

At the patient level, the significance of stem cell research lies in the prospect of therapies that are more intuitive to the body’s own processes. For instance, therapies based on stem cells could, in principle, awaken dormant repair mechanisms, guide the growth of new blood vessels in damaged tissues, or replace neurons lost in neurodegenerative conditions. These ideas are inspiring because they suggest a shift from repairing symptoms to restoring function at a system level. However, translating such concepts into proven medical treatments involves rigorous demonstration that the cells perform as intended, do so safely, and confer meaningful benefits that justify any risks. It is this cumulative body of evidence, including long-term follow-up and careful monitoring of patients, that ultimately determines whether a stem cell approach becomes a standard option rather than a research novelty. The field therefore operates within a framework that seeks to respect patient welfare, advance scientific knowledge, and maintain transparent communication about what is known, what remains uncertain, and what safeguards are in place to protect participants in experimental therapies.

Types of stem cells

Different kinds of stem cells offer distinct advantages for research and therapy. Embryonic stem cells, derived from early embryos, have the strongest potential to become any cell type, a property known as pluripotency. This versatility makes them valuable for studying early development, modeling diseases, and testing new drugs in a laboratory setting. Adult stem cells, sometimes called somatic stem cells, reside in specific tissues like bone marrow, adipose tissue, and the brain. They tend to be more limited in the range of cells they can become, a constraint that can be advantageous in therapeutic contexts because it reduces the risk of unexpected outcomes. Induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs, arise when ordinary adult cells are reprogrammed back into a pluripotent state. The advent of iPSCs provided a powerful workaround to some ethical and immunological concerns, since they eliminate the need for embryos and can be derived from a patient’s own cells. Each category carries its own set of technical challenges, regulatory considerations, and potential clinical applications. The choice among these options is guided by factors such as the intended tissue target, the risk profile for the patient, the feasibility of manufacturing at scale, and the strength of supporting evidence for safety and efficacy in given indications. As researchers refine differentiation protocols, they increasingly seek to guide stem cells along precise trajectories to produce mature, functional cells that mimic those found in health and disease. The nuanced understanding of these cell types has become a cornerstone of contemporary regenerative medicine and a cornerstone of thoughtful clinical trial design.

When scientists create undifferentiated stem cells and then steer them toward a specific lineage, they must ensure that the resulting cells closely resemble their natural counterparts in structure and function. This involves assessing not only the presence of key markers on the cell surface but also the cells’ performance in models of tissue function. In some contexts, researchers employ three dimensional culture systems or organoids—miniature, simplified versions of organs—to study how stem cells organize themselves and interact with neighboring tissues. The capacity to generate patient-specific cells through iPSCs also enables personalized models of disease, allowing researchers to compare how a patient’s cells respond to different drugs and therapies. The end goal across these approaches is to produce well-characterized, stable cell populations that can be reliably used in therapy or research. However, the journey from a test tube to a patient involves rigorous scaling, quality control, and verification that the cells retain their intended properties after transplantation or integration into native tissue. The field continues to refine these aspects to maximize the likelihood of beneficial outcomes while reducing risks.

Historical milestones and scientific progress

The story of stem cell research is a tapestry of incremental steps, unexpected discoveries, and ethically charged debates. In the mid to late twentieth century, early work on bone marrow transplantation and hematopoietic stem cells established a clinical foundation for using stem cells to treat blood disorders. The 1990s brought breakthroughs in deriving and characterizing embryonic stem cells, opening new vistas for understanding human development and disease at an unprecedented scale. The early twenty first century saw the emergence of induced pluripotent stem cells, a pivot that reshaped the ethical landscape by circumventing the need for embryos in many research contexts and enabling patient-specific studies. Over the years, researchers have demonstrated the capacity to differentiate stem cells into a growing array of mature cell types, including neurons, heart muscle cells, pancreatic cells, and cells that line blood vessels. Experimental success in animal models and early human trials has sharpened the sense that stem cell therapies can address conditions once deemed incurable, while also reinforcing the necessity of thorough safety validation. Milestones such as the development of standardized differentiation protocols, the creation of robust quality controls, and advances in genome editing have together elevated the scientific rigor of the field. The accumulating evidence has also illuminated the complexity of translating lab findings into durable therapies, underscoring the need for careful patient selection, precise dosing strategies, and rigorous long-term follow-up. Each milestone contributes to a map of the challenges and opportunities that define modern stem cell science as it moves toward broader clinical application.

Beyond the laboratory, the history of stem cell research is inseparable from conversations about policy, ethics, and public engagement. Debates about the source of cells, the moral status of embryos, and the equitable distribution of therapies have shaped funding, regulatory oversight, and the pace at which new treatments reach patients. In many regions, these issues led to the establishment of oversight bodies, guidelines for responsible conduct, and frameworks that balance innovation with patient protection. Over time, the field has learned important lessons about transparency, risk communication, and the need to distinguish between experimental science and proven clinical care. In contemporary practice, the narrative of stem cell research continues to evolve as new technologies emerge, as populations with diverse health needs participate in trials, and as scientists work to ensure that breakthroughs translate into meaningful health gains while maintaining the trust of the communities they serve.

Methods and technologies in stem cell research

Scientific progress in stem cell research rests on a toolkit of methods designed to isolate, culture, differentiate, and test stem cells under controlled conditions. Isolation techniques identify and collect stem cells from tissues, often using surface markers and sorting technologies to enrich the desirable cell population. Culture methods provide the supportive environments that allow stem cells to proliferate while maintaining their identity, using specialized media and extracellular matrices that mimic aspects of the body’s microenvironment. Differentiation protocols then guide these cells toward specific lineages by exposing them to defined signals, such as growth factors, small molecules, and changes in the physical conditions of the culture. Researchers continually refine these protocols to improve efficiency, safety, and the maturity of the resulting cells. In parallel, genetic and genomic tools enable precise manipulation of cells, aiding in the study of gene function, disease modeling, and the development of therapies. Genome editing technologies, including targeted nucleases and more recent high-precision approaches, hold the promise of correcting disease-causing mutations or enhancing cellular performance, while also raising important safety and ethical questions that must be addressed through rigorous testing and oversight. The creation of three dimensional tissue constructs, often described as organoids, provides a more realistic context to study cell behavior and tissue organization. Organoids can recapitulate essential features of organs, including their cellular diversity and some functional aspects, offering a bridge between simple cell cultures and whole-organism biology. Single-cell analysis techniques reveal heterogeneity within stem cell populations, helping scientists understand how individual cells respond to stimuli and how diverse outcomes emerge within a single culture. The convergence of these technologies creates a powerful pipeline for discovery, validation, and refinement, with the ultimate objective of delivering safe, effective therapies that align with biological reality rather than theoretical expectations. The field thus rests on a dynamic balance of creative experimentation and rigorous quality control, with ongoing attention to reproducibility and standardization across laboratories and clinical centers.

In addition to cellular manipulation, delivery systems and scaffolds play a crucial role when translating stem cell science into tissue repair strategies. Biomaterials capable of supporting cell survival, guiding differentiation, and promoting integration with host tissue are often used in conjunction with stem cells to improve outcomes. The immune response represents another important consideration; researchers must understand how transplanted cells interact with the recipient’s immune system and how to minimize rejection or unintended inflammatory processes. Strategies such as immune-compatible cell sources, immunomodulatory approaches, and localized delivery methods are among the tools used to address these challenges. Advanced imaging and monitoring techniques enable researchers and clinicians to observe the fate of transplanted cells over time, providing feedback that informs adjustments to therapeutic protocols. Together, these methodological advances equip the field to pursue more reliable, scalable, and patient-centered therapies, while also highlighting the need for ongoing transparency about risks, uncertain outcomes, and the limitations that accompany any emerging medical technology.

Applications in medicine

The potential medical applications of stem cell research span a broad spectrum of diseases and injuries, reflecting the fundamental capacity of these cells to participate in tissue formation, repair, and regeneration. In hematology, stem cell transplantation has become an established therapy for certain cancers and blood disorders, illustrating how stem cell biology can be harnessed to restore a functional blood system after intensive treatment. In cardiology, researchers are exploring whether stem cell–derived cardiac cells or supportive cell populations can improve heart function after myocardial injury, while acknowledging the complexities of ensuring stable integration with existing heart tissue and sustained benefit. In neurology, stem cell approaches hold the promise of replacing neurons or supporting neural networks in conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injuries, and certain forms of atrophy, though achieving durable functional recovery remains a central scientific hurdle. In ophthalmology, stem cells have moved into clinical practice for specific forms of macular degeneration and corneal diseases, offering the possibility of restoring visual function where conventional therapies have limited impact. In endocrinology, stem cells provide a route to generate insulin-producing cells for diabetes research and potential therapy, with careful attention to the risk of tumor formation and the challenge of mimicking the nuanced regulatory environment of pancreatic tissue. In orthopedics and wound care, stem cells contribute to the regeneration of bone, cartilage, and soft tissues, offering adjunctive strategies to accelerate healing and reduce chronic pain. Across these domains, researchers pursue not only the creation of new tissue but also the restoration of correct structure, organization, and function that align with healthy physiology. Real-world use of stem cell therapies often involves a combination of cell types, supportive materials, and imaging-based follow-up to assess efficacy and safety over time. The evolving clinical landscape emphasizes patient selection, individualized treatment planning, and robust data collection to build the evidence needed for broader adoption, always with an eye toward minimizing harm and maximizing meaningful health outcomes for diverse patient populations.

In practice, many stem cell therapies are still in the experimental or early clinical stages. Investigators frequently use stem cell–based approaches to model diseases in the lab, screen drugs for potential efficacy or toxicity, and gain insight into disease mechanisms. When moving toward patient-facing therapies, researchers design carefully controlled trials that test not only whether a treatment works but also how it compares with existing standards of care. These trials carefully monitor adverse events, durability of response, and potential long-term effects, recognizing that a therapy may appear beneficial in the short term but fail to deliver lasting improvements or reveal late complications. The regulatory framework guiding these activities emphasizes phased evaluation, standardized manufacturing practices, and rigorous quality assurance, ensuring that every step from cell sourcing to product delivery adheres to defined safety and efficacy criteria. The medical community continues to refine patient education and informed consent processes to ensure that individuals understand what a stem cell therapy can and cannot achieve, the uncertainties involved, and the responsibilities of participating in research or in receiving a novel treatment. As therapies mature, their integration into standard medical practice depends on accumulating robust, reproducible evidence that supports clear patient benefit while maintaining transparent risk disclosure and ongoing post-approval surveillance.

Ethical considerations and public discourse

Ethical questions surrounding stem cell research have shaped the field since its inception and continue to influence how it progresses. Debates about the use of embryonic tissues, the moral status of potential life, and the balance between scientific curiosity and social responsibility have required policymakers to craft frameworks that protect participants while allowing scientific exploration. Empowering patient autonomy means providing clear information about the purposes of research, the potential benefits, and the risks involved in experimental therapies, along with ensuring that participation is voluntary and informed. The emergence of patient-specific iPSCs has helped address some ethical concerns by reducing the need for embryos in many contexts, but new questions arise as the line between therapy and enhancement blurs and as genome editing enters clinical consideration. Public discourse also encompasses issues of access and equity. Advanced therapies may carry high costs or require specialized infrastructure, which can limit availability to certain populations. Societal conversations thus include not only technical feasibility but also economic planning, healthcare system readiness, and fair distribution of transformative health options. Responsible stewardship of stem cell science requires ongoing engagement with diverse stakeholders, transparent reporting of results—whether positive or negative—and a commitment to aligning scientific aims with the broader public good. Ethical reflection is not an impediment to progress but a compass that helps ensure that advances improve lives without compromising core moral commitments shared by societies.

Moreover, the field must confront concerns about consent, especially in contexts where tissue samples or cells are donated by patients or research participants. Clear governance structures, independent ethics committees, and culturally sensitive communication help ensure that individuals understand how their contributions may be used, including potential commercial applications. Attention to privacy and data protection is essential when genetic information and cell lines are linked to patient identities in research and clinical settings. The conversation also extends to the responsible use of stem cell technologies in education, media representations, and public expectations, acknowledging that sensational headlines can distort understanding and either inflame or dampen support for legitimate scientific work. By sustaining open, accurate, and compassionate dialogue, the scientific community can build trust and support informed decision-making about the direction and pace of stem cell research while remaining attentive to the diverse values and concerns that patients and communities bring to this work.

Regulatory landscape and clinical translation

Bringing stem cell therapies from the laboratory to patients requires a structured regulatory pathway designed to balance innovation with safety. Regulatory agencies around the world assess the quality, safety, and effectiveness of cell-based products before they can be marketed or used in clinical care. This involves evaluating how cells are sourced, processed, stored, and delivered, including tests for contamination, genetic stability, and the potential for unintended differentiation or tumor formation. Manufacturing standards, often described as good manufacturing practices, ensure that products are produced consistently and traceably. In clinical trials, researchers must demonstrate that a therapy meets predefined endpoints and that the benefits outweigh the risks for participants. The design of trials takes into account the unique characteristics of living cell products, including considerations related to dosing, routes of administration, and long-term monitoring for adverse effects. Regulatory review is complemented by post-market surveillance where applicable, as well as ongoing reporting requirements that contribute to the collective evidence base. The regulatory landscape also includes ethical oversight, ensuring that trial protocols respect patient autonomy, minimize risk, and deliver clear information about potential outcomes. Because stem cell therapies are often complex and personalized, regulatory processes sometimes adapt to accommodate innovative manufacturing approaches and fast-tracked pathways for promising therapies, while maintaining rigorous safeguards. This careful balance aims to foster responsible progress that can ultimately reach a broad patient population in a manner that is scientifically sound and ethically defensible.

Clinical translation is a stepwise process that begins with laboratory evidence and progresses through early safety studies into larger efficacy trials. Throughout this journey, researchers and clinicians engage with regulators, industry partners, and patient advocacy groups to align expectations and address practical concerns such as scalability, affordability, and access. The goal is not only to prove that a treatment works but also to demonstrate that it can be produced reliably at scale, with consistent quality and acceptable cost, and delivered in healthcare settings in a way that respects patient preferences and local standards of care. In some cases, stem cell therapies are integrated into existing treatment regimens as adjuncts rather than stand-alone cures, reflecting a nuanced understanding of how best to complement current practices. As science advances, regulators continue to refine guidelines for emerging modalities, such as gene-edited cells and combination products, ensuring that oversight keeps pace with innovation while preserving patient protection and public trust. The translational journey is thus characterized by collaboration across disciplines and institutions, transparent reporting, and a shared commitment to improving health outcomes in a responsible, scientifically rigorous manner.

Challenges, risks, and uncertainties

Despite dramatic progress, stem cell research faces a range of challenges that temper optimism with caution. A major concern is the risk that transplanted cells do not behave as intended, potentially forming unwanted tissue, failing to integrate, or triggering inflammatory or immune reactions. Long-term safety is a fundamental question, as some cellular therapies may have delayed adverse effects that only become apparent after years of observation. Manufacturing complexity presents another barrier, since producing large quantities of uniform, well-characterized cells is technically demanding and costly. Ensuring that produced cells retain their identity and function during storage, transport, and delivery is essential for consistent clinical performance. In addition, scientific questions persist about how best to mimic the natural tissue environment, how to direct differentiation with precision, and how to avoid unintended genetic changes that could have harmful consequences. Patient heterogeneity adds another layer of complexity; genetic background, age, comorbidities, and prior treatments can influence how a stem cell therapy performs in an individual. Ethical and social considerations intersect with these scientific hurdles, reminding stakeholders that access, affordability, and equity must be addressed as part of the responsible development of new therapies. The field therefore requires a vigilant safety culture, rigorous peer review, replicable results, and transparent reporting of both successes and setbacks to build a reliable foundation for future clinical adoption.

Additionally, public perception and misinformation can complicate the path forward. Misleading claims about cures or dramatic breakthroughs without robust evidence can create false hope or erode trust when promises fail to materialize. Scientists and clinicians acknowledge the responsibility to communicate clearly about what is known, what remains uncertain, and what steps are necessary before a therapy becomes widely available. Ongoing education for patients, clinicians, and policymakers helps ensure that expectations align with realistic timelines and outcomes. Finally, the field confronts the perennial challenge of funding, balancing investments in basic discovery with the requirements of rigorous translational research. Sustained support is needed to advance early-stage ideas through the necessary demonstrations of safety and effectiveness, while maintaining a patient-centered approach that prioritizes real-world benefits and minimizes harm. By openly addressing these challenges, the stem cell research community can continue to progress in a manner that is scientifically robust, ethically sound, and socially responsible.

The future of stem cell therapies

Looking ahead, the trajectory of stem cell therapies is shaped by ongoing innovations in cell biology, materials science, gene editing, and computational tools that help predict treatment outcomes. Advances in precision differentiation, scalable manufacturing, and patient-specific approaches hold promise for more individualized and durable interventions. The integration of stem cell technologies with routine medical practice could lead to new standards of care for chronic diseases, degenerative conditions, and injuries that currently limit quality of life. At the same time, researchers are refining strategies to minimize risk, such as improving immune compatibility, reducing tumorigenicity, and ensuring that transplanted cells perform in harmony with the body’s signaling networks. The future may also bring new modalities that combine cellular therapy with supportive devices, drug regimens, or bioengineered scaffolds to create synergistic effects. As therapies mature, collaboration among scientists, clinicians, regulators, industry, and patient communities will be essential to translate advances into accessible, affordable, and ethically grounded treatments. The promise of stem cell research thus rests on a framework of rigorous science, thoughtful governance, and a steadfast commitment to enhancing human health while honoring shared values and informed consent. By maintaining this balance, the field aspires to move from remarkable potential to reliable, life-changing medicine that benefits people across diverse backgrounds and life circumstances.