Introduction to metastatic cancer and chemotherapy

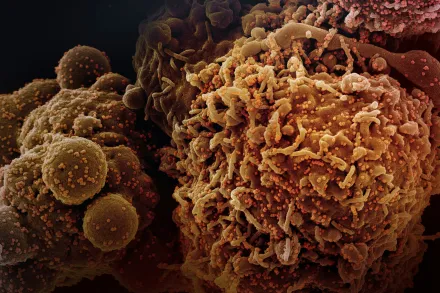

Metastatic cancer represents a state in which malignant cells have spread beyond their site of origin and established new foci in distant tissues or organs. This systemic nature of metastasis means that disease can no longer be addressed solely by local treatments such as surgery or localized radiation. In this context, chemotherapy emerges as a cornerstone of systemic therapy that travels through the bloodstream to reach scattered tumor deposits. The overarching goal of chemotherapy in metastatic disease is to slow tumor growth, reduce tumor burden, prolong survival, and sometimes alleviate symptoms that compromise quality of life. Yet the landscape is complex because different cancers behave in unique ways, and the biology of each tumor influences how it responds to cytotoxic drugs. In addition to tumor characteristics, patient factors—including performance status, organ function, comorbidities, nutritional state, and personal preferences—play a crucial role in shaping therapeutic decisions. The ethical balance between potential benefit and risk of harm lies at the heart of the clinical enterprise, especially when the aim includes maintaining functional independence and minimizing treatment-related distress. This introductory terrain sets the stage for exploring how chemotherapy functions within a metastatic setting and how clinicians integrate it with other strategies to optimize outcomes for patients facing advanced cancer.

In considering chemotherapy for metastatic disease, it is essential to acknowledge that cytotoxic agents do not selectively attack only malignant cells; they affect rapidly dividing cells across the body. This broad activity underpins both the therapeutic effect and the adverse event profile of chemotherapy. The concept of treatment benefit in the metastatic setting often hinges on multiple dimensions: tumor response, duration of control, symptom relief, delay of complications, and the potential to bridge patients toward other interventions that may be more effective or better tolerated. The patient’s voice remains central in this process, guiding expectations and clarifying what constitutes meaningful benefit. Throughout the journey, supportive care measures—such as antiemetics to prevent nausea, growth factors to mitigate troughs in blood counts, and strategies to preserve organ function—are woven into the treatment plan to reduce harm and sustain function. The dynamic relationship between tumor biology, pharmacology, and patient resilience creates a landscape in which chemotherapy is no longer perceived as a single, uniform intervention but as a personalized, evolving approach tailored to the individual patient and the specific cancer type involved.

Historical perspective and evolution of chemotherapy for metastasis

The story of chemotherapy in cancer care began with a surprising observation in the mid twentieth century that certain chemical agents could dramatically alter the course of disease. Early discoveries, often rooted in historical contexts such as exposure to environmental compounds or responses to infections, led to the first therapeutic regimens that could impact tumor growth systemically. Over decades, the development of more potent alkylating agents, antimetabolites, platinum-based drugs, and microtubule inhibitors transformed the prognosis of several metastatic cancers. The field progressed from palliative aims to a broader spectrum that included durable disease control, conversion of some metastatic lesions to a curable or potentially controllable state, and prolonged survival with an acceptable balance of toxicity. The evolution also reflected a growing understanding of tumor heterogeneity and the diversity of disease biology across cancer types. Researchers learned that combination regimens, when designed with complementary mechanisms of action and non-overlapping toxicities, could achieve greater tumor kill than single agents alone. This insight reshaped the standard of care and led to a rhythm of regimens that could be adapted to the metastatic setting, where ongoing treatment decisions are often made in the context of response, side effects, and patient goals. The historical arc thus frames chemotherapy as a mature, adaptable modality that interacts with scientific advances to remain relevant in modern oncology, even as new paradigms emerge around targeted therapies and immunotherapy.

From the early era of broad cytotoxic exposure to current practice characterized by precision in drug selection and sequencing, the history of chemotherapy in metastatic disease also reflects a deepening appreciation for patient experience. Early regimens were associated with harsh toxicities that sometimes limited their use, but improvements in supportive care have considerably expanded the therapeutic window. As survival improved, clinicians increasingly integrated chemotherapy with imaging-based response assessment, quality-of-life metrics, and patient-reported outcomes to sculpt treatment courses that align with what patients value most. The historical narrative is therefore not only about drugs and doses but about a shift toward thoughtful, patient-centered care in which chemotherapy serves as one instrument within a broader spectrum of systemic therapies. This evolution underscores the ongoing need to balance disease control with the preservation of function, independence, and dignity in the face of metastatic cancer.

Mechanisms of action and biological rationale for systemic chemotherapy in metastasis

Chemotherapy comprises a family of agents that interfere with fundamental cellular processes essential for tumor cell survival. The mechanistic diversity among these agents includes disruption of DNA replication and repair, interference with mitotic progression, inhibition of essential metabolic pathways, and the induction of oxidative stress that tumors may be ill equipped to manage. Alkylating agents create crosslinks in DNA that hinder replication and transcription, producing lethal genomic instability in dividing cells. Antimetabolites mimic natural substrates of nucleotide synthesis and DNA replication, thereby sabotaging essential biochemical processes. Plant-derived agents, including microtubule inhibitors and topoisomerase inhibitors, disrupt critical elements of cell division or DNA topology, triggering cell death. Platinum-based compounds, with their DNA-damaging properties, have a broad spectrum of activity across many tumor types and often produce synergistic effects when combined with other cytotoxic or targeted therapies. These mechanisms provide a rationale for using chemotherapy in metastatic disease: the agents are systemic and can reach disseminated tumor cells irrespective of their location, exerting cytotoxic effects on multiple sites simultaneously. Yet the systemic reach of these drugs also means that normal rapidly dividing cells—such as those in the bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, skin, and hair follicles—are susceptible to toxicity, underscoring the need for carefully titrated regimens and robust supportive care.

Biological reasoning for chemotherapy in metastasis also includes considerations of microenvironmental constraints that influence drug delivery and tumor sensitivity. For instance, the irregular blood supply within tumors can create regions of hypoxia and acidity that affect drug penetration and efficacy. The presence of cancer stem-like cells, stromal elements, and immune components in the tumor microenvironment further shapes response patterns. In some settings, cytotoxic therapy may act not only by directly killing tumor cells but also by disrupting supportive networks that enable metastatic growth, thereby indirectly limiting disease progression. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of each drug, including tissue distribution, metabolism, and clearance, guide their use across different organs and stages of disease. In the metastatic landscape, dosing schedules that optimize cumulative exposure while minimizing peak-related toxicity can influence outcomes, particularly when patients have variable organ function or competing health concerns. This mechanistic tapestry explains why chemotherapy remains a mainstay in many settings, even as newer therapies emerge with more selective targets and distinct toxicity profiles.

Finally, the theoretical synergy between chemotherapy and other treatment modalities is grounded in biology. Some regimens may sensitize tumors to immune-mediated attack or to targeted inhibitors, while others may reduce tumor burden to allow more meaningful assessments of subsequent interventions. The underlying biology supports a nuanced approach in which chemotherapy is chosen not only for its direct cytotoxic potential but also for its capacity to enable or complement other strategies. Clinicians often weigh these mechanistic considerations alongside practical factors such as patient tolerance, prior exposures, and the pattern of disease to craft a regimen that fits the individual metastatic context.

Clinical decision making in metastatic disease

Clinical decision making in metastatic cancer is a multidimensional process that integrates tumor biology, disease kinetics, patient physiology, and personal values. The pace of disease progression—whether rapid, slow, or variable—helps determine how urgently therapy is needed and how aggressively it should be pursued. Some cancers exhibit brisk growth and widespread dissemination at diagnosis, prompting systemic therapy at once to attempt rapid disease control, alleviate symptoms, and potentially improve survival trajectories. In other scenarios, slower-growing tumors may allow a more deliberate approach that emphasizes quality of life and careful monitoring while reserving cytotoxic therapy for periods when it is most likely to yield meaningful benefit. Across all situations, performance status and organ reserve serve as essential compass points. An ECOG or Karnofsky performance score, alongside measurements of kidney and liver function, informs whether a patient can tolerate standard regimens or whether dose modifications and supportive measures are required. Comorbid conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or chronic infections, influence regimen choice and the risk of cumulative toxicity, particularly in settings where treatment may be prolonged or repeated.

Another critical axis in decision making is the likelihood that chemotherapy will meaningfully alter the disease course. For some tumor types, cytotoxic regimens have demonstrated robust activity with documented responses and survival benefits in metastatic contexts. In others, the gains may be modest and primarily related to symptom control or stabilization, especially when disease biology is driven by mechanisms less susceptible to DNA-damaging strategies. Physicians commonly engage patients in shared decision making, explaining the expected benefits, potential side effects, and the practical implications of therapy on daily life. They also discuss goals of care, clarifying whether the priority is symmetrical disease control, symptom relief, postponement of complications, or a plan to proceed with alternative therapies available through clinical trials or targeted agents. The decision-making process is iterative: as the disease evolves, response rates change, and patients’ preferences and tolerances shift, clinicians adapt treatment plans accordingly. In this sense, chemotherapy in the metastatic setting is a dynamic, patient-centered enterprise that evolves with both scientific advancements and the lived experience of those facing cancer.

Care coordination across a multidisciplinary team enhances the quality of decision making. Medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, surgical specialists when relevant, palliative care professionals, pharmacists, nurses, nutritionists, and social workers contribute to a holistic assessment. This team-based approach helps ensure that therapy aligns with the patient’s goals, mitigates risk, and addresses practical needs such as transportation, financial considerations, and caregiver support. The integration of palliative care early in the metastatic trajectory has been shown to improve symptom management and satisfaction with care, underscoring that chemotherapy decisions are not solely about extending life but also about sustaining the ability to live well for as long as possible. Ultimately, the art of clinical decision making in metastatic disease rests on balancing realistic expectations with compassionate communication, a process that honors both scientific rigor and human experience.

Common regimens and their roles across cancer types

Across diverse cancers, chemotherapy regimens in the metastatic setting are chosen with attention to the tumor’s biology, prior treatments, and the patient’s overall condition. In some malignancies, cytotoxic regimens are the backbone of therapy because of their proven capacity to reduce tumor burden, relieve symptoms, and extend survival. In others, cytotoxic drugs are used in combination with agents that target specific molecular abnormalities or with immunotherapies that harness the patient’s own immune system. The interplay between cytotoxic therapy and targeted or immune-based strategies helps tailor treatment to the particular cancer type and its stage. For instance, in certain solid tumors such as colorectal or breast cancer, platinum- or taxane-based regimens may remain standards of care for metastatic disease, often in combination schedules designed to maximize efficacy while maintaining tolerability. In hematologic malignancies, cytotoxic chemotherapy can induce rapid disease control, sometimes achieving remission that allows consolidation with additional modalities. Throughout these variations, the principles of carefully planned dosing, monitoring for adverse effects, and prompt management of complications remain universal. Treatment decisions frequently reflect the balance between achieving meaningful tumor control and preserving quality of life, an equilibrium that shifts as new evidence emerges from clinical trials and real-world experience.

The selection of a regimen is rarely static. Clinicians consider response patterns, duration of benefit, and the tolerability of therapy, recognizing that prolonged exposure to cytotoxic agents can lead to cumulative toxicities that challenge ongoing treatment. In some cases, initial regimens are followed by planned transitions to alternative agents or supportive measures that maintain disease control while reducing adverse effects. The goal is to maintain an active state of treatment that patients can tolerate for as long as it provides advantages, rather than to push for maximal cytotoxic intensity that could erode function and well-being. When appropriate, pharmacogenomic information and biomarkers guide choices, guiding selection toward regimens with higher probabilities of efficacy for a given molecular context. In all instances, the clinician strives to craft a plan that honors patient preferences, preserves autonomy, and aligns with realistic expectations about what chemotherapy can achieve in the metastatic setting.

It is also important to recognize that some regimens are especially suited to transitional goals, such as bridging to surgical debulking, regional therapies, or participation in clinical trials. In such scenarios, systemic chemotherapy can shrink disease burden enough to enable local treatments that might achieve better local control or render a patient eligible for a trial that offers access to innovative therapies. The diversity of regimens across cancer types reflects the breadth of chemotherapy’s role in metastatic disease: it remains a versatile, adaptable tool, used alone or in combination, to influence the disease course in ways that harmonize with each patient’s clinical trajectory and personal priorities.

Balancing efficacy and toxicity in the metastatic setting

The metastatic context places particular emphasis on balancing therapeutic benefit against the risk of harm. Efficacy signals—such as tumor shrinkage, stabilization of disease, improvement of symptoms, and measurable survival gains—must be weighed against chemotherapy-induced adverse effects. Common toxicities include suppression of the bone marrow leading to fatigue and infection risk, mucositis that impairs eating and speaking, gastrointestinal disturbances that affect nutrition, neuropathic pain or tingling that can limit function, and organ-specific dysfunction such as kidney or liver impairment. The risk profile is influenced by drug class, dose intensity, schedule, cumulative exposure, and individual patient factors. Proactively addressing these risks through supportive care measures is essential. Anti-nausea medications, growth factor support when appropriate, dose modifications, and careful monitoring of blood counts and organ function help maintain a tolerable balance between benefit and burden. In patients with limited life expectancy or substantial frailty, the threshold for continuing or intensifying cytotoxic therapy may be higher, prompting a focus on symptom relief and functional preservation rather than aggressive disease targeting. The clinical philosophy in these cases centers on patient autonomy, realistic expectations, and transparent communication about what can be achieved and what remains uncertain.

Quality of life stands as a central determinant in treatment planning. Clinicians increasingly quantify patient-reported outcomes and functional status as part of the decision-making process. Treatments that yield modest tumor responses but substantial fatigue, nausea, or cognitive effects may not be desirable for some patients, whereas others may prioritize even small gains if they translate into improved day-to-day functioning. Dose modifications, shorter treatment cycles, or switches to different agents may be employed to preserve quality of life without sacrificing disease control. Across all these decisions, the patient’s values, social support, and goals for care guide the chosen path. The art of balancing efficacy and toxicity thus emerges as a nuanced negotiation, tailored to the unique constellation of disease biology, patient physiology, and personal meaning attached to treatment outcomes.

Supportive care planning is inseparable from this balance. Proactive management of side effects, vaccination considerations, infection prevention, nutritional support, physical activity, sleep hygiene, and mental health resources contribute to sustaining the overall well-being of patients undergoing chemotherapy for metastatic disease. The aim is not only to extend life but to preserve the capacity to engage in meaningful activities, maintain independence where possible, and reduce the burden of treatment-related suffering. In this light, chemotherapy is viewed not simply as a sequence of drug administrations but as an integrated program that includes symptom control, psychosocial support, and ongoing alignment with the patient’s evolving preferences and clinical realities.

Resistance and personalization

Tumor cells adapt to chemotherapy through a variety of mechanisms that blunt or negate drug efficacy over time. Genetic changes, epigenetic alterations, and shifts in tumor microenvironments contribute to intrinsic or acquired resistance. The heterogeneity within and between tumor lesions can lead to differential sensitivity, with some sites responding while others remain refractory. Personalization of therapy seeks to address this complexity by identifying patient-specific factors that influence response. Genomic profiling, when available, can reveal actionable alterations that guide targeted or combination approaches designed to overcome resistance. Circulating tumor DNA and other biomarker tools offer dynamic windows into tumor evolution, offering the possibility of timely treatment adjustments as the disease mutates. In parallel, insights into pharmacogenomics illuminate how individual metabolism and drug transport influence exposure and toxicity, informing dose modifications to optimize benefit while reducing harm. The convergence of resistance biology and personalization thus frames a proactive strategy: anticipating resistance, integrating alternative therapies earlier in the disease course, and maintaining flexibility to adjust plans as tumor and patient biology evolve. This forward-looking approach seeks to sustain meaningful disease control in the face of adaptive cancer, rather than persisting with a one-size-fits-all regimen that becomes progressively less effective.

Personalization in this context is not limited to molecular characteristics. It encompasses the patient’s goals, tolerance for side effects, and life circumstances. A regimen that is scientifically potent may be inappropriate for a person who values daily functioning and independence over marginal extensions of life. Conversely, a patient who prioritizes maximal disease control may accept higher toxicity if it yields a meaningful reduction in symptoms or a longer period of stability. Clinicians therefore translate complex scientific information into personalized care plans that honor both the biology of the tumor and the lived reality of the patient. This personalized approach extends to trial enrollment, where eligibility criteria may reflect molecular features, disease behavior, or specific prior treatments, offering access to novel therapies that can address resistance patterns and potentially improve outcomes beyond standard options. In sum, managing resistance and embracing personalization are central to extending the relevance and effectiveness of chemotherapy for metastatic cancer in the modern era.

Impact on quality of life and palliative considerations

In metastatic cancer care, the impact of chemotherapy on quality of life is a pivotal consideration. While cytotoxic therapy can control disease and relieve tumor-related symptoms, it can also introduce new burdens that affect sleep, energy, appetite, cognitive function, and daily routines. The balance between symptom relief and treatment-related distress is delicate and varies from patient to patient. Palliative care principles emphasize early integration, focusing on symptom management, psychosocial support, and advance care planning in parallel with disease-directed therapies. This integration helps patients navigate complex decisions, clarifies goals of care, and supports family members and caregivers who bear responsibility for daily care. The goal is to optimize the patient’s functional status and comfort, enabling meaningful engagement with loved ones and activities that bring purpose and joy, even in the context of advancing disease. Short-term improvements in symptoms, such as decreased pain from tumor burden or improved appetite following effective therapy, can be meaningful milestones, while the potential for cumulative toxicity requires ongoing vigilance and timely interventions. The quality of life conversation is ongoing and adapts to shifts in health status, treatment response, and the patient’s personal priorities, ensuring that care remains aligned with what matters most to the patient’s life and dignity.

Palliative considerations also include planning for adverse events and ensuring access to supportive resources. Nutrition, physical therapy, social work services, spiritual care, and transportation assistance are frequently integrated into the treatment course to support resilience and adaptability. When disease progression occurs or the anticipated benefit of therapy diminishes, conversations about goals of care, comfort-focused strategies, and end-of-life preferences become essential. In this way, chemotherapy in a metastatic setting is not solely about disease-directed cytotoxicity but about a comprehensive approach that respects patient autonomy, minimizes suffering, and upholds the values and wishes of the person facing cancer. Through thoughtful planning and compassionate communication, care teams strive to maintain dignity and meaning for patients and their families as the disease evolves.

Emerging strategies and integration with targeted therapies and immunotherapy

The oncology landscape is increasingly characterized by convergence between traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy and newer modalities that target specific molecular pathways or harness the immune system. In metastatic disease, chemotherapy often serves as a bridge or complement to these newer strategies. For example, cytotoxic regimens can debulk tumor mass and reduce immunosuppressive tumor burden, potentially enhancing the effectiveness of immunotherapies that rely on a robust immune response. At the same time, certain targeted therapies and cellular immunotherapies can reshape the tumor microenvironment in ways that make cancer cells more susceptible to subsequent cytotoxic kill, suggesting optimal scheduling and sequencing that maximize synergy while limiting overlapping toxicities. Metronomic dosing strategies, in which lower, more frequent dosing is used to minimize peak toxicity while preserving anti-tumor activity and potentially modulating angiogenesis, illustrate how therapeutic philosophy evolves to balance efficacy with patient well-being. These evolving paradigms underscore the importance of comprehensive molecular profiling, clinicians' vigilance for signals of benefit or harm, and the flexibility to adapt plans as science advances.

Additionally, combination trials exploring the integration of cytotoxic drugs with novel agents aim to expand the therapeutic reach of chemotherapy in metastatic cancer. The rationale rests on the idea that cytotoxic therapy can disrupt tumor defenses and expose cancer cells to immune recognition or targeted inhibitors. Such combinations require careful monitoring because additive toxicities can arise when agents with overlapping adverse effect profiles are used together. Prospective research and robust clinical experience are essential to delineate which patients will benefit most from these strategies, how to optimize dosing schedules, and how to manage unique toxicities that emerge from combination regimens. In this sense, the role of chemotherapy in metastatic cancer is not diminished but rather reframed within a broader, more sophisticated therapeutic ecosystem that aims to tailor treatments to each patient’s biology and preferences while embracing the promise of future innovations.

Beyond the laboratory and clinic, real-world data and patient experiences contribute to refining how chemotherapy is used in metastatic disease. Observational studies, registries, and pragmatic trials help illuminate how treatments perform in diverse populations outside of tightly controlled clinical trials. They reveal aspects such as accessibility, adherence challenges, and the socioeconomic determinants of care that influence outcomes. Incorporating these insights into practice fosters an approach that is both scientifically grounded and socially responsive, ensuring that advances reach a broad spectrum of patients who can benefit from them. In this evolving landscape, chemotherapy remains a dynamic component of metastasis management, compatible with advances in precision medicine and patient-centered care while continuing to address the fundamental questions of when to initiate therapy, when to adjust, and how to balance hope with realism.

Practical considerations for patients and caregivers

For patients facing metastatic cancer, practical realities shape the experience of chemotherapy as much as biology does. Logistics surrounding treatment delivery, scheduling, and follow-up require careful planning. Infusion center visits, educational resources, medication access, and coordination among multiple specialists can be complex, and families often assume substantial caregiving responsibilities. Financial considerations, including medication costs, transportation, and time away from work, contribute to the overall burden and influence decisions about the appropriateness and intensity of therapy. Proactive planning, clear communication with the healthcare team, and utilization of social work and patient navigation services can mitigate these challenges. Nutrition and physical activity play supportive roles in maintaining resilience, and patients are encouraged to engage in gentle, individualized routines that support energy levels and mood. Communication strategies that acknowledge fears, preferences, and expectations help foster trust and enable shared, informed decisions that honor what matters most to the person living with metastatic cancer. Caregiver well-being is also essential, with resources and respite options that help sustain caregiving over the potentially long course of disease management.

Adherence to treatment plans, understanding potential side effects, and recognizing when to seek timely medical advice are practical skills that empower patients to participate actively in their care. Education about signs of infection, bleeding, dehydration, or significant organ dysfunction supports early intervention and can prevent complications from escalating. As therapy progresses and disease biology shifts, patients and clinicians revisit goals of care and adjust plans to reflect evolving priorities. In this ongoing dialogue, chemotherapy in metastatic cancer is positioned not as a static prescription but as a responsive, compassionate care pathway that remains aligned with the patient’s life context, values, and aspirations. By sustaining open communication, providing robust supportive care, and honoring patient autonomy, the healthcare team helps preserve dignity and function, even as disease challenges persist.