Overview of the heart and surgical goals

The heart is a muscular organ that functions as the central pump of the circulatory system, propelling blood through a network of vessels that nourish tissues and sustain life. Its anatomy includes four chambers, two atria and two ventricles, separated by valves that regulate the flow of blood between chambers and into the main arteries. The coronary arteries arise on the surface of the heart and deliver oxygen rich blood to the heart muscle itself, enabling sustained contraction and endurance. Cardiac surgery is performed when structural problems hinder the heart’s ability to pump efficiently, when valve function deteriorates, when there are blockages in coronary vessels that limit blood flow, or when congenital or acquired defects disrupt normal heart rhythms or chamber anatomy. The overarching goals of cardiac surgery are to relieve symptoms, improve heart function, prevent further damage, and extend life by restoring stable hemodynamics, reducing inflammatory responses associated with disease, and enabling patients to regain a higher quality of daily living. In many cases, surgery is complemented by careful medical therapy and a structured rehabilitation plan that emphasizes gradual physical recovery, nutrition, and management of risk factors such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, obesity, and smoking. The decisions about operating procedures are driven by precise imaging data, the patient’s functional status, the anticipated survival benefit, and the likelihood of achieving durable improvement with a given technique. As techniques evolve, surgeons increasingly tailor approaches to the patient’s unique anatomy and disease pattern, harmonizing medical management with mechanical support when necessary to achieve the best possible outcome.

Preoperative assessment and planning

Before any cardiac procedure, a comprehensive evaluation is undertaken to determine suitability, risk, and the expected trajectory of recovery. A patient history review focuses on prior heart problems, diabetes, kidney function, liver function, respiratory status, and prior surgeries. The physical examination targets chest shape, lung capacity, and signs of heart failure that could influence anesthesia or surgical access. Noninvasive tests such as electrocardiograms, echocardiography, and stress imaging provide critical information about chamber function, valve integrity, wall motion abnormalities, and the presence of scar tissue. In some cases, cardiac MRI or CT imaging adds a detailed view of anatomy, including the aorta, coronary arteries, and adjacent structures. Laboratory studies assess blood counts, electrolyte balance, kidney function, and the ability to tolerate surgery, while pulmonary evaluations gauge lung efficiency and potential respiratory complications. The planning phase also involves discussing the anticipated procedure, the expected length of hospital stay, and the rehabilitation pathway after surgery. Risk assessment tools that consider age, body mass index, prior heart interventions, and comorbid conditions help guide the choice of technique and whether additional support, such as temporary mechanical assistance, may be advisable. Informed consent is an essential component of planning, ensuring that the patient understands the reasons for surgery, the steps involved, potential complications, and the likelihood of benefit given the specific clinical context. A personalized plan is then developed that aligns the surgical strategy with the patient’s goals, the surgeon’s expertise, and the available resources at the care center.

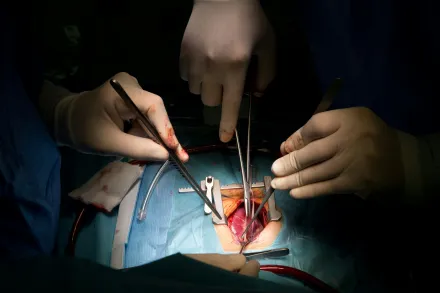

Surgical approaches and techniques

Cardiac surgery can be performed through several access routes and with different respiratory and circulatory support strategies. The traditional approach involves a median sternotomy, which provides wide access to the heart and great vessels by splitting the sternum. This approach allows surgeons to work with clear visibility and precise control when repairing or replacing valves, addressing multiple areas of the heart in a single operation, or performing complex reconstructions of the aorta. In addition to this conventional access, surgeons increasingly employ minimally invasive techniques that use smaller incisions and specialized instruments to reach the heart through intercostal spaces or narrow pathways. These approaches are particularly common for selected valve procedures or revascularization in patients who benefit from reduced trauma to the chest wall, diminished postoperative pain, and faster initial recovery, although they demand specialized training and equipment and may involve longer operative times depending on the anatomy and the procedure. Robotic systems and enhanced imaging technologies further extend the reach of minimally invasive approaches, offering heightened precision in selected cases and allowing for delicate maneuvers around delicate structures, while maintaining patient safety and stable surgical exposure. The choice of technique is influenced by the disease pattern, the patient’s body habitus, prior surgeries, and the surgeon’s experience. Cardiopulmonary bypass, the use of a heart-lung machine to take over the duties of circulation and oxygenation, is employed in many procedures to provide a bloodless field and a motionless heart. In other situations, surgeons opt for off-pump techniques that perform coronary revascularization without stopping the heart, thereby avoiding the systemic effects of bypass in certain patients. During the time on bypass, a cardioplegic solution is infused to arrest the heart gently and protect the heart muscle during manipulation. Techniques to protect organs during surgery, including careful temperature management and monitoring of blood flow, are integral to all approaches, and anesthesia teams coordinate closely with surgeons to maintain stable physiology throughout the operation. In every scenario, meticulous planning, precise hemodynamic control, and readiness to adapt to intraoperative findings underpin a successful procedure and reduce the risk of complications.

Common cardiac procedures

Cardiac surgery encompasses a spectrum of operations designed to correct structural problems, restore function, and relieve symptoms. Each major category requires distinct skills, instruments, and intraoperative decisions that influence outcomes and recovery. In many centers, teams include cardiac surgeons, anesthesiologists, perfusionists, nurses, and rehabilitation specialists who work together from preoperative assessment through recovery. The following sections explore several principal procedures and the core ideas behind each, emphasizing what patients and families should understand about indications, goals, and expected pathways of care. Although the specifics vary by patient, the unifying themes are the restoration of normal blood flow, the stabilization of valve and chamber function, and the protection of the heart muscle during periods of surgical intervention. Across procedures, teams monitor for bleeding, infection, organ dysfunction, rhythm disturbances, and response to exertion, adjusting therapy to promote durable results and minimize the impact on quality of life. In CABG procedures the goal is to reestablish blood flow to regions of the heart that are deprived of oxygenated blood due to blocked arteries; in valve procedures the aim is to restore proper valve motion and efficiency, preventing backward flow and reducing the workload on the heart; in aortic surgery attention centers on repairing or replacing portions of the aorta that have stretched or torn under pressure; in rhythm management surgeries the focus is on interrupting abnormal circuits that drive arrhythmias; in transplant and assist device interventions the objective is to replace or augment the heart’s pumping capacity when the native organ can no longer sustain circulation. Each operation carries specific risks and expected benefits, which surgeons discuss with patients in detail as part of the shared decision making that guides modern cardiac care.

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)

Coronary artery bypass grafting remains one of the most common cardiac operations and a cornerstone of revascularization therapy for advanced coronary disease. The principle behind CABG is to bypass narrowed segments of coronary arteries by placing grafts that reroute blood from the aorta to downstream heart muscle, thereby improving oxygen delivery and alleviating angina. Grafts can be harvested from the saphenous vein in the leg or from arteries such as the internal mammary arteries that begin inside the chest cavity. The diagnostic workup identifies which arteries are critically obstructed and determines whether multiple bypasses are needed to restore a balanced blood supply to the heart. The grafting strategy is tailored to the patient’s anatomy: in some cases a single very important blockage can be relieved with one graft, while in others several vessels require attention. On-pump CABG uses cardiopulmonary bypass to provide a still heart and a bloodless field, allowing meticulous suturing and precise graft placement. Off-pump CABG avoids the bypass machine, which can shorten recovery in certain patients but may require more complex stabilization of the heart during suturing. Outcomes depend on factors such as the extent of coronary disease, the quality of the target vessels, and the patient’s overall health. The long-term benefits include improved exercise tolerance, reduced hospitalizations for heart failure, and, for many individuals, improved survival. The postoperative period involves careful rhythm monitoring, management of pain, gradual reintroduction to activity, and consideration of risk factors aimed at preventing new blockages in the native arteries or vein grafts. Among the important considerations are the durability of the grafts, the potential for graft closure over time, and the impact on the patient’s lifestyle and medications, including antiplatelet therapy and lipid control. In appropriate candidates CABG can dramatically improve heart function and quality of life, especially when combined with optimization of risk factors and ongoing medical therapy.

Valve repair and valve replacement

Valve disease, whether congenital, degenerative, or due to rheumatic or infectious processes, disrupts the normal opening and closing of one or more heart valves, creating abnormal blood flow and imposing extra work on the heart. Valve procedures aim to restore unidirectional flow, reduce regurgitation or stenosis, and preserve myocardial function. Valve repair seeks to correct the existing tissue and mechanics of the patient’s own valve, maintaining native tissue whenever feasible, which can offer advantages in durability and reduced need for long term anticoagulation. When repair is not possible or less durable, valve replacement becomes the appropriate strategy, employing either mechanical prostheses or bioprosthetic devices derived from animal tissue or human donors. Mechanical valves tend to be durable and long lasting, but require lifelong anticoagulation to prevent clots, whereas bioprosthetic valves generally have a limited need for anticoagulation and may degrade over time, especially in younger patients, potentially necessitating future intervention. The decision between repair and replacement, and the choice of prosthesis type, depends on the valve involved, the degree of tissue damage, the patient’s age, lifestyle, and the presence of other illnesses. Surgeons use precise measurements and imaging to assess leaflet motion, annulus size, and chordal structures, guiding the operation with a goal of achieving a well matched, leak-free valve that functions reliably under the heart’s pressures. Postoperative care emphasizes valve function monitoring with imaging and echocardiography, management of anticoagulation as appropriate, and strategies to maintain heart rhythm stability and blood pressure within safe ranges to protect the new or repaired valve as it integrates with the surrounding tissue. Patients often experience a noticeable reduction in symptoms such as shortness of breath and fatigue after a successfully implemented valve procedure, and many resume daily activities with greater ease and confidence in their cardiovascular health.

Aortic surgery and root procedures

The aorta is the main channel through which blood leaves the heart and travels to all organs. When parts of the aorta become weakened, dilated, or dissected, the risk of rupture or catastrophic bleeding rises, and surgical intervention becomes essential. Aortic surgery encompasses repair of aneurysms that bulge along the ascending, aortic arch, or descending segments, as well as procedures that replace portions of the aorta or the aortic root itself. The Bentall procedure, a well-known root replacement operation, exemplifies how surgeons address both the aorta and the aortic valve in a single, integrated strategy. In other scenarios, surgeons deploy specialized grafts to reinforce or replace the affected segment, reattach coronary arteries, and re-establish stable blood flow to downstream vessels. Such operations require careful planning of cannulation strategies for the heart-lung machine, precise reconstruction of the aortic arch, and meticulous attention to the proximity of major vessels that feed the brain and other organs. The complexity of aortic procedures demands not only technical mastery but also careful risk assessment regarding bleeding, spinal cord protection, and the potential for organ ischemia during periods of altered circulation. Successful outcomes hinge on accurate preoperative imaging, thoughtful sequencing of steps during the operation, and robust postoperative management to monitor graft integrity, blood pressure control, and neurological function. Recovery from aortic surgery often involves a longer hospital stay and tailored rehabilitation that emphasizes gradual activity resumption, wound healing, and vigilant surveillance for changes in the grafts and heart function over time.

Arrhythmia surgery and rhythm management

Arrhythmias arise when the electrical signals that coordinate the heart’s rhythm become abnormal, leading to heartbeats that are too fast, too slow, or irregular. In selected patients, surgical approaches can interrupt or modify the circuits responsible for these disturbances, restoring a stable rhythm and enhancing cardiac efficiency. The Maze procedure is a foundational rhythm operation that creates precisely placed scar tissue within the atria to disrupt rogue electrical pathways while preserving the heart’s essential conduction system. Variants and adjunctive procedures may involve ablation lines delivered through energy sources or direct surgical modification during concomitant procedures such as valve repair or coronary surgery. For some patients, minimally invasive or catheter-based ablation provides a rhythm management option that reduces symptomatic episodes and improves exercise capacity. In addition to procedural ablation, the management of arrhythmias often includes the implantation of devices such as pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), which help regulate heart rate and protect against dangerous rhythms. The integration of surgical rhythm control with device therapy requires close coordination between surgeons, electrophysiologists, and anesthesiologists to ensure seamless tuning of pacing and rhythm correction in the perioperative period and beyond. The long-term success of rhythm interventions depends on durable electrical remodeling, careful management of medications, and regular monitoring to detect recurrence or device-related issues that may necessitate adjustments in therapy.

Transplantation and assist devices

For patients with end-stage heart failure where the native heart is no longer able to sustain life, transplantation offers the possibility of renewed circulation and improved quality of life. Heart transplantation involves replacing the diseased heart with a donor heart, a process that requires meticulous donor selection, recipient evaluation, immune compatibility matching, and lifelong immunosuppressive therapy to prevent rejection. The perioperative period is marked by complex coordination to minimize ischemic injury to the donor heart and to manage immune responses as the new heart begins to function within the recipient’s chest. In parallel with transplantation, mechanical assist devices such as ventricular assist devices (LVADs) provide supplemental pumping capacity for patients who are not immediate candidates for transplant or who await donor organs. LVADs can support one or both ventricles and may be used as a bridge to transplantation or as destination therapy in patients for whom a transplant would not be appropriate. The use of these devices requires ongoing medication management, regular imaging, and vigilant attention to infection risk and device durability. The ultimate goals are to relieve symptoms of heart failure, improve end-organ function, and extend meaningful survival, all within a framework that balances surgical risk, device reliability, and the patient’s values and goals for care. The care pathway includes comprehensive rehabilitation, nutrition optimization, and psychosocial support to help patients adapt to a new reference framework for living with a transplanted heart or a powered assist device.

Preparation and perioperative care

Successful cardiac surgery depends not only on the technical execution in the operating room but also on careful preparation and postoperative care. The anesthesia team coordinates the induction of anesthesia, the management of sedation, analgesia, fluid balance, and respiratory support to ensure stable physiology before, during, and after the operation. Intraoperative monitoring includes continuous imaging, electrocardiography, invasive blood pressure measurement, and rhythm surveillance to guide decisions in real time. After the operation, patients are typically transferred to an intensive care unit where specialized nurses and physicians monitor heart function, breathing, blood pressure, kidney function, and potential complications. Pain control strategies aim to minimize discomfort while enabling early mobilization and deep breathing to prevent lung complications. Early rehabilitation emphasizes gentle movements, coughing techniques, and patient education about breathing exercises and the importance of pulmonary hygiene. Nutritional support is tailored to promote healing, maintain energy, and support immune function, particularly in patients with chronic disease or malnutrition risk. Physicians also review medication regimens to optimize heart function, control blood pressure, and modulate clotting risk, taking into account the recent surgical changes and any implanted devices. The transition from hospital to home involves structured planning, follow-up appointments, and clear instructions about activity limits, wound care, signs of infection or complications, and avenues for urgent care should new symptoms arise. A robust perioperative program integrates physical therapy, occupational therapy, nutrition counseling, and psychosocial support to maximize the patient’s recovery trajectory and long-term cardiovascular health.

Risks, complications, and prognosis

All cardiac surgeries carry inherent risks, which can vary with the patient’s age, comorbid conditions, and the complexity of the procedure. Potential complications include bleeding requiring transfusion, infection of the chest wound or mediastinitis, stroke due to disruption of blood flow to the brain, kidney injury that may complicate fluid management, and heart rhythm disturbances that necessitate temporary or permanent treatment. Reoperation may be required if bleeding persists or if there is failure of a repaired or replaced valve or graft. Specific procedures carry their own profile of risks; for example, valve replacement may lead to anticoagulation-related bleeding or prosthetic dysfunction over time, while bypass surgery may present with graft occlusion, low blood pressure, or myocardial injury. Long-term prognosis is influenced by the success of the procedure, the quality of the native tissue, the patient’s adherence to medical therapy, and the management of risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and lipid disorders. In many cases, patients experience meaningful symptom relief, improved exercise tolerance, and a better overall sense of well-being after recovery and rehabilitation. Regular follow-up with imaging and clinical evaluation is essential to ensure that the heart remains stable and that any late changes in function are identified promptly and managed appropriately. The evolution of surgical techniques, improved perioperative care, and advances in medical therapy continue to shape positive outcomes for a broad spectrum of patients requiring cardiac interventions.

Recovery and lifestyle after cardiac surgery

Recovery after cardiac surgery is a gradual process that unfolds over weeks to months and requires clear expectations, ongoing medical support, and adherence to a structured rehabilitation program. In the early postoperative period, patients are monitored closely for signs of infection, issues with wound healing, and complications such as pleural effusion or atelectasis that can affect breathing. Pain management is carefully tailored to allow deep breathing and coughing, which are essential to preventing lung complications. Physical therapy and gentle activity are introduced progressively to rebuild strength, improve circulation, and restore functional capacity. Nutrition plays a key role in healing, with attention to adequate protein intake and balanced calories to support tissue repair and energy needs during recovery. Many patients experience improvements in chest tightness, fatigue, and shortness of breath as heart function stabilizes and healing progresses. Long-term lifestyle changes form the cornerstone of durable success; these include engaging in regular aerobic exercise within the guidance of clinicians, following a heart healthy diet, maintaining a healthy weight, quitting tobacco use if applicable, managing stress, staying adherent to prescribed medications, and routinely monitoring blood pressure, lipid levels, and glucose control as appropriate. Cardiac rehabilitation programs provide structured support, education, and supervised exercise to help patients navigate the adjustment from hospital to home, gradually reintegrating into work and social activities. Patients should also remain vigilant for warning signs such as fever, increasing chest pain, new shortness of breath, rapid heart rate, or swelling in the legs, and seek medical attention if these occur. The overarching objective is to empower patients to participate actively in their health, maintain gains achieved through surgery, and sustain a heart healthy lifestyle that mitigates the likelihood of recurrence or the progression of disease.

Emerging trends and future directions

The field of cardiac surgery is continually advancing, driven by innovations in imaging, materials, and accelerated recovery pathways. Newer valve technologies include durable bioprosthetic and transcatheter options that offer less invasive replacement while reducing the overall recovery burden for selected patients. Robotics and enhanced visualization systems enable surgeons to perform intricate maneuvers through smaller incisions, expanding the possibilities for repair and reconstruction while reducing trauma to the chest wall. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine hold promise for remodeling damaged heart tissue or developing valves that can better integrate with patient physiology. Computational planning, three dimensional printing, and virtual simulation allow teams to rehearse complex operations and tailor interventions to the unique anatomy of each patient. Personalized medicine, including targeted pharmacotherapy and risk stratification based on genetic and molecular factors, supports more precise decision making about when to operate and which techniques are most likely to yield durable results. As technology evolves, the collaboration among surgeons, anesthesiologists, perfusionists, nurses, and rehabilitation specialists deepens, fostering a holistic approach that emphasizes safety, efficiency, and patient-centered outcomes. The continuous refinement of perioperative care, postoperative rehabilitation, and long-term management will likely lead to shorter hospital stays, quicker return to daily life, and improved survival for many individuals facing cardiac disease. In this evolving landscape patients and families benefit from comprehensive education, transparent discussions about options, and shared decision making with clinicians who integrate cutting edge science with the highest standards of clinical practice.