Antiviral drug resistance is a phenomenon that arises when the agents designed to suppress viral replication become less effective or fail to halt the spread of infection. This occurs through changes in viral genetics or in the way viruses interact with the drugs used to treat them. The phenomenon is not limited to a single virus or a particular class of medications; it is a broad challenge that touches many infections, from seasonal influenza to chronic infections such as HIV and hepatitis. A careful understanding of resistance requires integrating principles from virology, pharmacology, epidemiology, and clinical practice, along with ongoing surveillance and research.

To appreciate why antiviral resistance matters, it helps to distinguish between intrinsic resistance, which is inherent to a viral strain due to its natural biology, and acquired resistance, which develops after exposure to antiviral drugs. Intrinsic resistance may occur when a virus naturally carries mutations that reduce drug binding or alters its life cycle to be less susceptible to intervention. Acquired resistance, by contrast, emerges during treatment when selective pressure favors variants that can survive in the presence of the drug. In either case, the result is reduced drug effectiveness, which can lead to prolonged illness, increased transmission, and the need for alternative therapies.

The factors that drive resistance are diverse and interconnected. High virus replication rates, large viral populations within an individual, and genetic diversity provide a fertile ground for resistance mutations to appear. The pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the drug, including how well it penetrates tissues and whether drug concentrations remain sufficient at the site of replication, shape the likelihood that resistant variants will emerge. Environmental and social factors, such as incomplete adherence to therapy, drug interactions, and delays in initiating treatment, further contribute to the risk landscape of resistance in communities and healthcare settings.

From a historical perspective, resistance has appeared across different antiviral classes and viruses, underscoring the need for vigilance and innovation. In influenza, resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors has been documented, sometimes in a minority of circulating strains, raising concerns about the durability of these drugs during outbreaks. In the case of human immunodeficiency virus, long-term therapy with combination regimens has dramatically transformed outcomes, yet resistance remains a central consideration in selecting regimens, interpreting diagnostic tests, and planning retreatment. Understanding these experiences informs contemporary strategies for preservation of drug efficacy and optimization of patient care.

Mechanisms of resistance in viruses

At the heart of antiviral resistance are genetic changes that alter the target of the drug, the drug itself, or the pathways that the virus uses to replicate. Mutations in viral enzymes or structural proteins that are required for replication can decrease the binding affinity of a drug, reduce its ability to inhibit activity, or permit the enzyme to function with the drug bound in a way that diminishes inhibitory effects. These mutations may occur in regions of the protein that are directly contacted by the drug or in nearby sites that influence the shape and dynamics of the active site. The net effect is a shift in the drug’s potency and a need to adjust treatment strategies accordingly.

Another important mechanism involves changes that enable the virus to bypass the step that the drug targets. Some drugs act by blocking a specific step in the replication cycle; if the virus can circumvent that step through alternative pathways or accessory proteins, the antiviral effect may be blunted. This concept of bypass pathways highlights the complexity of viral replication, where redundancy and flexibility can undermine single-agent interventions. In some viruses, mutations can also alter the sequence or structure of drug targets in a way that reduces drug affinity while preserving essential biological functions, a balance that can be difficult for the virus to maintain without tradeoffs in fitness.

Compartmentalization and pharmacokinetic factors add another layer to resistance. The body presents various sites where viruses replicate, sometimes in tissues that are poorly penetrated by certain drugs. If drug concentrations in these sanctuaries are suboptimal, resistant variants can gain a foothold. Additionally, some viruses establish latent or delimited reservoirs where replication is minimal or intermittent; in such contexts, selective pressure may be uneven, allowing resistant variants to emerge and persist when therapy is adjusted or stopped. These spatial and temporal dynamics complicate the interpretation of treatment responses and the design of robust regimens.

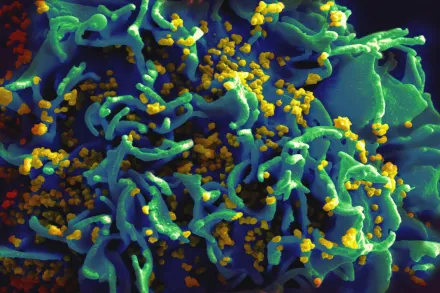

Viral population dynamics within a host also contribute to resistance through the concept of quasispecies. RNA viruses, in particular, exhibit high mutation rates, generating a swarm of related genomes. Within this swarm, a minority of variants may harbor resistance mutations. When antiviral therapy is applied, the drug selects for these resistant genomes, which can then become predominant. The interplay between mutation, selection, and genetic drift shapes the trajectory of resistance and can vary between individuals, viruses, and treatment scenarios. This complexity emphasizes the importance of comprehensive testing and adaptive management of therapy.

Factors driving resistance in clinical settings

Adherence to treatment regimens is a central determinant of resistance risk. When patients miss doses or stop therapy prematurely, drug levels may fall below the threshold needed to suppress viral replication, allowing time for resistant variants to emerge. Even modest lapses in adherence can alter the balance between susceptible and resistant populations, particularly for viruses with rapid replication cycles. Clinicians strive to design regimens that are forgiving in the real world, offering pharmacokinetic buffers or long-acting formulations to maintain effective suppression even when doses are occasionally delayed.

Pharmacokinetic interactions between drugs and patient factors such as age, organ function, and concurrent medications can modify drug exposure. Suboptimal drug concentrations can create a breeding ground for resistance, while excessive exposure may increase toxicity without necessarily improving outcomes. Individualized dosing, therapeutic drug monitoring when feasible, and careful consideration of drug interactions are key strategies to minimize resistance in clinical practice. These principles apply across chronic infections and acute outbreaks alike, reinforcing the need for precise, patient-centered management.

Monotherapy, or the use of a single antiviral agent, is associated with a higher risk of resistance compared with combination therapy, especially for viruses capable of rapid mutation. Combination regimens, by targeting multiple steps of the replication cycle, reduce the probability that a single mutation will confer cross-resistance to all components. This approach has become a cornerstone of therapy for complex infections such as HIV and hepatitis C, where the goal is to create a high barrier to resistance. The design of such regimens requires a careful balance of potency, tolerability, and drug interactions to sustain long-term control of viral replication.

Impact on treatment strategies and patient care

Understanding resistance informs the selection of initial therapy and the plan for monitoring response. Clinicians must anticipate the potential for resistance to undermine treatment and incorporate diagnostic tests that detect known resistance mutations or phenotypic changes in the virus. Genotypic assays identify specific genetic alterations associated with reduced drug susceptibility, while phenotypic assays measure the functional response of viruses to antiviral compounds. The choice between these testing modalities depends on the virus, the available assays, and practical considerations in the healthcare setting.

Resistance also shapes retreatment strategies. When resistance emerges, clinicians may switch to alternative agents with different targets or mechanisms, or introduce additional drugs to broaden coverage and raise the genetic barrier to resistance. In some cases, resistance testing guides the selection of regimens that preserve future options by avoiding cross-resistance with drugs that may be needed later. This adaptive approach requires close collaboration among clinicians, microbiologists, and pharmacologists, as well as timely access to diagnostic tools and a range of therapeutic options.

Public health implications of resistance extend beyond individual patients. Resistant viruses can circulate within communities, complicating outbreak control and increasing the burden on healthcare systems. Surveillance programs track trends in resistance, informing guidelines for empiric therapy, vaccine design, and infection prevention measures. The integration of clinical data with population-level analyses helps health authorities anticipate emerging threats, allocate resources, and support research into next-generation antivirals and alternative strategies to reduce transmission and disease burden.

Global surveillance and public health implications

Global surveillance networks play a critical role in detecting resistance patterns early and guiding stewardship efforts. By collecting standardized data on antiviral use, treatment outcomes, and resistance mutations, these systems enable scientists and policymakers to identify hotspots, track the spread of resistant strains, and assess the impact of interventions. The sharing of high-quality data across borders accelerates the refinement of treatment guidelines and supports the development of regionally appropriate strategies that account for local resistance pressures and population dynamics.

Public health responses to resistance require an integrated set of actions. These include rational prescribing practices to minimize unnecessary exposure, vaccination programs to reduce disease burden and transmission, and infection control measures in healthcare and community settings to limit the spread of resistant viruses. In addition, research funding and regulatory pathways that expedite the evaluation of new antivirals, combination regimens, and host-targeted approaches are essential. A resilient health system uses surveillance, innovation, and equitable access to keep resistance under control and to protect vulnerable populations from severe disease.

Future directions in overcoming antiviral resistance

Advances in antiviral research are expanding the toolkit available to fight resistance. Broad-spectrum antivirals that target conserved aspects of viral replication hold promise for reducing the impact of resistance across multiple viruses, while host-directed therapies aim to disrupt host factors essential for viral replication, potentially lowering the risk of resistance arising in the virus itself. Such strategies require careful consideration of safety, as interventions that affect host pathways can carry off-target effects and must be optimized to minimize harm while providing clinical benefit.

Innovations in drug design, including allosteric inhibitors, high-barrier compounds, and multi-target agents, seek to make it harder for resistance to arise. Long-acting formulations and sustained-release delivery are being explored to improve adherence and maintain drug levels that suppress viral replication consistently. In parallel, advances in diagnostics, such as rapid genotypic testing and point-of-care resistance assays, will empower clinicians to tailor therapy in real time, reducing unnecessary exposure and preserving drug options for the future.

Artificial intelligence and systems biology are increasingly being applied to predict resistance trajectories, optimize dosing, and simulate the impact of different treatment strategies in populations. These tools can help identify optimal drug combinations, anticipate compensatory mutations, and guide public health decisions. The convergence of scientific innovation with strong stewardship, equitable access, and robust surveillance promises to slow resistance, extend the lifespan of effective therapies, and improve outcomes for patients around the world.