Targeted therapy represents a distinct approach to cancer treatment that focuses on specific molecules and cellular processes that drive the growth and survival of cancer cells. Unlike traditional chemotherapy that often affects both malignant and healthy cells, targeted therapies aim to disable the tumor’s own machinery while sparing much of the normal tissue, thereby offering the potential for effective treatment with different side effects. This approach relies on understanding the genetic and molecular landscape of a patient’s cancer and translating that knowledge into a therapeutic plan that interrupts critical signaling networks, metabolic dependencies, or cellular interactions that enable tumor progression. At its core, targeted therapy looks for those vulnerabilities that cancer cells have acquired through genetic changes, and then designs interventions to exploit those weaknesses with precision and selectivity. The field grew out of advances in genomics, proteomics, and molecular biology, and it continues to evolve as researchers map the complex web of interactions that sustain cancer cells while identifying biomarkers that predict response to a given drug. The resulting strategies are not one-size-fits-all; they are framed by the unique biology of each tumor and are chosen in tandem with diagnostic tests that reveal which targets are present and functionally important in a patient’s cancer. This personalized approach holds the promise of more effective control of disease with fewer generalized toxicities, though it also invites ongoing monitoring as tumors adapt and new targets emerge. In practical terms, practitioners increasingly teach patients that targeted therapy is not simply a single drug or a single mechanism, but a dynamic program that combines molecular insight with therapeutic precision to disrupt the cancer’s growth circuits in specific, actionable ways.

Foundations of Targeted Therapy

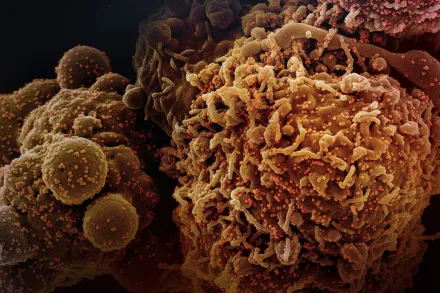

Targeted therapy rests on identifying aberrant proteins or pathways that cancer cells rely on more than normal cells do. Many cancers acquire mutations, amplifications, or structural rearrangements that produce proteins that behave abnormally, or that convert normal signaling networks into persistently active circuits. By profiling tumors with molecular tests, clinicians can discover these targets and then select therapies designed to bind to the abnormal protein directly or to disrupt the downstream signals that promote proliferation, survival, invasion, and resistance to death. The success of this strategy depends not only on the presence of a target, but also on how essential that target is to the cancer’s biology, whether the tumor has backup routes to bypass the blockade, and how accurately a patient’s cancer matches the biomarker the drug was designed to exploit. The practical upshot is that a patient’s tumor must be characterized with precision diagnostic tools, and the resulting biomarker information must be integrated into a treatment plan that aligns with the drug’s mechanism of action. When these elements align, a therapy can function as a surgical strike within the tumor’s signaling architecture, slowing or halting malignant growth while preserving more normal cell function than would be typical with nonselective cytotoxic agents.

Mechanisms of Action

Most targeted therapies fall into two broad categories: monoclonal antibodies that bind to proteins on the surface of cancer cells and small molecules that interfere with intracellular enzymes and signaling proteins. Monoclonal antibodies can recognize a specific protein with high precision, tagging cancer cells for immune attack, blocking essential receptor functions, or delivering cytotoxic payloads through conjugates. Small molecule inhibitors, by contrast, are typically chemical compounds that can enter cells and block the activity of enzymes, kinases, or other components of signaling pathways that cancer cells rely on for growth. Both strategies share a common goal: to disrupt the signals that tell cancer cells to divide, to resist death, and to migrate to new sites. In many cases, targeted therapies also exploit the dependency of tumors on particular metabolic or assembly processes, thereby depriving cancer cells of the resources they require to sustain abnormal growth. The resulting disruption can slow disease progression, shrink tumors, or convert a previously uncontrolled process into a controllable one. The exact outcome depends on the tumor type, the compensatory networks available within the cancer cells, and how well the patient tolerates the treatment. Across the landscape of targeted therapy, success hinges on continuous refinements in drug design, pharmacodynamics, and the ability to monitor whether the intended target remains engaged and functionally relevant inside the tumor microenvironment.

Blocking Receptors on the Cell Surface

One prominent approach uses monoclonal antibodies to block receptors that sit on the surface of cancer cells. When these receptors normally receive growth signals, their activity can be hijacked by cancer cells to promote unchecked division. By binding to the receptor, an antibody can prevent the natural ligand from engaging the receptor, halt downstream signaling, recruit immune effector mechanisms to attack the cell, or deliver cytotoxic agents directly to the cancer cell. This strategy is especially effective in tumors that overexpress a particular receptor or rely on receptor-mediated signaling for survival. The success of receptor blockade often depends on how essential the receptor is for the tumor’s continued growth and how well the tumor depends on the signaling pathway that the receptor mobilizes. In several well-established cancers, blocking surface receptors has become a standard of care because it interrupts a critical lifeline for the malignant cell while preserving much of the normal tissue that does not depend on the same deregulated signaling cascade. The approach can be tailored further by incorporating antibody-drug conjugates that deliver toxins precisely to cancer cells, amplifying the direct impact on malignant cells while limiting systemic exposure to the drug’s toxic payload.

Enzymes and Signaling Pathways Inside the Cell

Small molecule inhibitors penetrate cancer cells to target kinases and other intracellular enzymes that act as switches in signaling networks. By inhibiting a single enzyme, the cancer cell’s workflow can be disrupted in a way that reduces proliferation, induces stress, or sensitizes the cell to death. Many cancers become dependent on specific kinases after acquiring mutations, and tumors often become addicted to particular signaling pathways. Inhibitors designed to fit the altered active site of a mutant enzyme can shut down these dysregulated circuits, thereby arresting tumor growth. In addition, some small molecules influence transcriptional programs or metabolic enzymes that support the cancer cell’s altered state. The ability to design drugs that selectively bind mutant proteins while sparing the normal counterparts is a central driver of the targeted therapy paradigm. The deployment of these inhibitors depends on precise biomarker diagnostics to confirm that the cancer’s biology matches the drug’s intended target, which is why companion tests and genetic profiling have become foundational in modern oncology practice. Outside of direct enzyme inhibition, researchers are also exploring drugs that disrupt protein-protein interactions and destabilize oncoproteins, adding layers of complexity to how targeted therapy can be harnessed against cancer cells.

Angiogenesis and the Tumor Blood Supply

Certain targeted therapies aim to halt the growth of new blood vessels that tumors require to expand and metastasize. Tumors often secrete signals that recruit blood vessels, creating a blood supply that delivers oxygen and nutrients necessary for growth. Inhibiting this process, known as anti-angiogenesis therapy, can slow tumor progression by starving cancer cells and altering the tumor microenvironment. These strategies typically involve blocking vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or its receptor, thereby reducing the formation of new vessels and changing the vascular architecture within and around the tumor. The downstream effects include decreased tumor perfusion, enhanced sensitivity to other treatments, and a shift in how cancer cells manage hypoxic stress. While anti-angiogenesis therapies have shown clinical benefit across multiple cancer types, tumors can adapt by finding alternative routes to supply blood or by altering their resilience to low oxygen. This means that combination strategies and careful patient monitoring are often necessary to sustain the therapeutic effect and minimize adverse vascular events in sensitive populations.

Precision Medicine: Matching Therapy to the Biomarker

Precision medicine hinges on aligning a patient’s treatment with the specific molecular fingerprint of their cancer. By identifying actionable alterations such as gene mutations, gene amplifications, fusions, or aberrant protein expression, clinicians can select therapies that directly target the tumor’s vulnerabilities. This approach moves beyond tissue type and focuses on the underlying biology, recognizing that the same molecular abnormality can drive cancer in different organs and that different tumors may share a common target. The process begins with diagnostic testing, which may include sequencing of DNA and RNA, assessment of protein levels, and functional assays to gauge dependency on particular pathways. The resulting biomarker profile informs decisions about which targeted agent or combination regimen is most likely to yield meaningful control of disease with an acceptable safety profile. As technologies evolve, the repertoire of detectable targets expands, enabling more patients to access therapies tailored to their tumor’s unique biology and paving the way for adaptive strategies that evolve with the cancer over time.

Testing and Biomarker Discovery

Biomarker testing is a cornerstone of implementing targeted therapy in clinical practice. Standard panels may screen for well-established alterations, while comprehensive sequencing can uncover rare or novel mutations that render a patient eligible for a specific drug or an experimental agent in a trial. Beyond DNA mutations, researchers are increasingly evaluating gene expression patterns, protein activation states, and epigenetic modifications as potential biomarkers. The interpretive process requires careful consideration of tumor heterogeneity, sample quality, and the evolving nature of cancer under treatment pressure. Some targets exist only in a subset of cells within a tumor, or their activity may fluctuate over time, necessitating repeat testing at progression or after therapy to decide whether to switch strategies or to add complementary agents. The clinical value of biomarkers is amplified when results guide not only drug selection but also dosing strategies, monitoring plans, and evaluation criteria for response, enabling a structured approach to measure benefit and adjust therapy as needed.

Resistance and Adaptation in Cancer

Cancer cells are highly adaptable, and even the most precisely targeted therapies can lose effectiveness as tumors acquire resistance. Mechanisms of resistance include secondary mutations that prevent drug binding, activation of parallel signaling branches that bypass the inhibited target, amplification of compensatory pathways, or changes in drug transport and metabolism that reduce intracellular concentrations. The clinical implication is that response to a targeted therapy is not always permanent, and progression on a targeted agent may reflect the tumor’s reconfiguration to survive the blockade. Understanding these resistance patterns has spurred the development of next-generation inhibitors that can overcome many single-point mutations, as well as combination approaches that block multiple nodes of a signaling network at once. Ongoing research emphasizes sequencing strategies that anticipate resistance, the integration of molecular surveillance during treatment, and the use of adaptive trial designs that permit timely changes in therapy based on real-time molecular data. Ultimately, the goal is to stay ahead of the cancer’s capacity to adapt by anticipating likely escape routes and deploying multi-pronged strategies that preserve tumor control for longer periods.

Combination Strategies and Sequencing

Given the finite durability of responses to many targeted therapies, clinicians increasingly explore combination regimens to enhance efficacy and delay resistance. Combinations may pair a targeted agent with another targeted drug that shuts down a complementary pathway, with immunotherapy to mobilize the patient’s own immune system against the cancer, or with conventional chemotherapy or radiation in carefully chosen contexts. The rationale is to attack the cancer on multiple fronts, such that cancer cells have fewer opportunities to adapt. The sequencing of therapies—deciding which drug to start, which to switch to upon progression, and how to integrate biomarker information at each step—requires close monitoring of tumor dynamics and patient tolerability. Successful combinations balance additive or synergistic anti-tumor activity with manageable safety profiles, while staying responsive to new biomarker discoveries and evolving standards of care. In practice, this means that every patient’s treatment plan is revised in light of molecular findings, clinical response, and the appearance of new targets, creating a dynamic therapeutic journey rather than a fixed sequence of drugs.

Side Effects and Safety Considerations

Targeted therapies often have a different safety profile than traditional chemotherapy, reflecting their more selective actions. Some therapies produce minimal short-term toxicity because they spare many normal tissues, while others can cause specific adverse events related to the target’s role in normal physiology. For example, inhibitors of blood vessel formation can lead to hypertension or thrombotic risk, while blockade of cardiac signaling pathways may affect heart function in susceptible individuals. Skin, gastrointestinal, and liver-related effects are also common with various agents. Importantly, because targeted therapies act on defined molecular processes, side effects can sometimes be predictable and manageable with dose adjustments, supportive care, or temporary treatment interruptions. Ongoing pharmacovigilance, patient education about warning signs, and proactive management are essential components of safe and effective use. The goal is to maximize the therapeutic benefit while minimizing disruption to quality of life, recognizing that careful patient selection and monitoring are as critical as the drugs themselves in achieving durable disease control.

Clinical Practice and Access

In modern oncology, choosing a targeted therapy is a collaborative process that involves oncologists, pathologists, genetic counselors, and often multidisciplinary care teams. Access to targeted therapy depends on accurate biomarker testing, timely interpretation of results, and the availability of approved drugs or clinical trials. Many patients qualify for targeted therapies through companion diagnostic tests developed alongside a drug, and sometimes access is facilitated by insurance coverage, patient assistance programs, or trial participation. Clinical trials play a vital role in expanding the evidence base for targeted approaches, testing new targets, and refining combinations that may offer benefits beyond current standards of care. For patients, being informed about the rationale for a targeted treatment, the expected benefits, the potential risks, and the plan for monitoring response is essential for shared decision making and sustained engagement with therapy, especially when dealing with complex disease courses or evolving treatment landscapes.

Future Directions in Targeted Therapy

The horizon of targeted therapy continues to broaden as scientists decode more detailed maps of oncogenic signaling networks, resistance mechanisms, and tumor microenvironment influences. Advances in genomic technologies, single-cell analysis, and computational biology are enabling more precise patient stratification and the discovery of previously unrecognized targets. Proximity-based approaches that disrupt protein complexes, degraders that remove oncogenic proteins from cells, and therapies that reprogram the immune milieu within tumors are areas of active exploration with the potential to complement or even surpass current strategies. Precision oncology is also moving toward real-time molecular monitoring, where liquid biopsies and circulating biomarkers inform dynamic treatment adjustments, possibly even before radiographic progression becomes evident. In this evolving landscape, the core principles remain clear: identify a cancer’s essential vulnerabilities, design agents that engage those vulnerabilities with high specificity, and integrate molecular insight into a therapeutic plan that can adapt as the disease biology evolves. The promise of targeted therapy lies in translating deep molecular understanding into practical, personalized care that improves outcomes while preserving patient well-being across diverse cancers and diverse patient journeys.