In modern medicine, stem cell therapy represents a class of approaches that leverage the unique capabilities of living cells to influence healing, repair, and regeneration. At its most fundamental level, this field rests on the idea that certain cells retain the ability to renew themselves and to give rise to other specialized cell types found in the body. When scientists and clinicians use these cells in therapeutic contexts, they aim to either replace damaged tissues with functional cells or to create an environment that supports the body's own restorative processes. This initial overview opens a window into the biology of stem cells, the practical methods used to deliver them, and the ways in which these cells can shape recovery in organs ranging from joints to the brain and beyond.

Foundations of stem cells and their unique properties

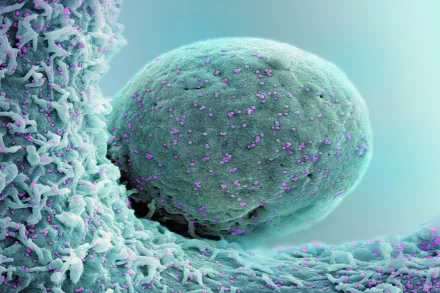

Stem cells are defined by two core traits: self renewal and the capacity to differentiate into multiple specialized cell types. Some stem cells are pluripotent, meaning they can become nearly any cell type in the body, while others are multipotent, restricted to a family of related cells. In clinical contexts, adult stem cells, such as mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow or adipose tissue, are commonly used because they are more readily available and carry a lower ethical burden than embryonic sources. Induced pluripotent stem cells, generated in the laboratory by re programming mature cells, offer a route to cells with broad differentiation potential while enabling patient matching. The microenvironment, or niche, in which stem cells reside profoundly shapes their fate, guiding whether they remain quiescent, proliferate, or differentiate into needed cell types. In the body, stem cells exist not to replace every lost cell all at once, but to participate in ongoing maintenance and repair, responding to signals that arise from injury, stress, or metabolic demands. When used therapeutically, scientists seek to harness these properties in a controlled, safe manner, often by selecting cells with defined marker profiles and proven potency for the intended tissue target.

How therapies are delivered

Delivery of stem cells in a therapeutic setting encompasses a spectrum of strategies designed to place the right cells at the right location with a viable survival plan. Autologous therapies use a patient’s own cells, which reduces the risk of immune rejection and often obviates stringent donor matching, whereas allogeneic therapies employ donor cells that are carefully screened and prepared to minimize immune incompatibility. The route of administration matters a great deal: intravenous infusion can allow cells to circulate and home to injury sites, local injections deliver cells directly where tissue damage is greatest, and intra arterial or intracoronary routes target specific vascular territories. In some cases, cells are combined with biomaterials or scaffolds that provide structural support, guiding growth and integration into the surrounding tissue. Manufacturing quality, cell viability, and precise dosing are critical to achieving predictable effects, and advanced processing steps are designed to preserve functional properties while eliminating contaminants. The end goal is a product that can persist long enough to influence healing without provoking adverse reactions, while maintaining regulatory compliance and ethical standards.

After administration: homing, engraftment, and paracrine signaling

Once delivered, stem cells interact with a dynamic, injury induced microenvironment. A key challenge is homing, the process by which circulating cells detect chemical cues released by damaged tissues and migrate toward the site of injury. This involves complex interactions with the endothelium, adhesion molecules, chemokines, and the extracellular matrix, all coordinated to promote entry into the tissue. Even when cells do not permanently engraft, their presence can modulate the local biology. A major mechanism of action is paracrine signaling, whereby stem cells release a sophisticated mix of growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles that influence neighboring cells, dampen excessive inflammation, recruit resident progenitor cells, and stimulate angiogenesis. These secreted factors can also alter the immune environment, promoting more constructive healing while limiting tissue destruction. In many clinical settings, observed benefits correlate more strongly with these temporary, signaling mediated effects than with long term replacement of cells by the transplanted population.

The repair mechanisms at work

Repair in stem cell therapies unfolds through a constellation of processes that collectively restore tissue function. Differentiation into replacement cells is one pathway, but in many tissues this occurs infrequently or modestly; more often, cells provide a supportive niche that enables native repair mechanisms to proceed. Immunomodulation is a central feature, with stem cells capable of tempering inflammatory cascades that would otherwise perpetuate tissue damage. They can promote the formation of new blood vessels to restore perfusion, a process known as angiogenesis, which is essential in healing ischemic injuries or chronically damaged tissue. The remodeling of the extracellular matrix, regulation of fibroblast activity, and the recruitment of resident stem or progenitor cells all contribute to rebuilding tissue architecture. By adjusting the local milieu, stem cells create a window of opportunity for healing rather than attempting a blunt mechanical replacement of tissue.

Therapeutic targets in different tissues

In orthopedic conditions such as osteoarthritis or focal cartilage injuries, stem cell therapy aims to support cartilage matrix restoration, reduce pain pathways, and influence inflammatory mediators that drive degeneration. In cardiovascular disease, particularly after myocardial injury, the objectives include improving perfusion, stabilizing scar formation, and encouraging survival of at risk cardiomyocytes through trophic signaling. Neurological applications seek to protect neurons, replace damaged neural elements where feasible, and modulate the inflammatory response that often accompanies central nervous system injuries. In liver disease, skin wounds, and other organ systems, stem cells may help reestablish vascular networks, promote regeneration, and bias healing toward more functional tissue rather than scar tissue. Across these diverse targets, the practical reality is that stem cell therapies rely on a combination of direct cell replacement and subtle, orchestrated signaling that guides resident cells toward organized repair rather than haphazard regeneration.

Safety, regulation, and patient considerations

Safety is a central focus in stem cell therapy, and the risk profile can vary widely depending on cell type, source, processing, and the disease being treated. Potential concerns include infection, unintended tissue formation, abnormal immune responses, and, in some contexts, tumorigenicity if cells acquire growth advantages. Because products differ across laboratories and clinics, regulatory oversight emphasizes rigorous validation of identity, purity, potency, and sterility, as well as demonstration of a favorable risk benefit balance for a given indication. Patients should seek treatment at centers with transparent reporting of treatment protocols, oversight by relevant regulatory authorities, and access to clear informed consent that outlines what is known, what remains uncertain, and the realistic expectations for outcomes. While autologous therapies often carry fewer immunologic risks, allogeneic approaches require thoughtful donor selection and compatibility considerations, and both require ongoing monitoring for adverse events. A well informed patient discussion should cover the stage of evidence for a specific condition, the anticipated mechanism of action, and how the therapy integrates with standard care options.

Manufacturing and quality control

The journey from a patient’s tissue or a donor sample to a therapeutic cell product passes through a sequence of tightly regulated steps designed to ensure consistency and safety. Cells are isolated, characterized, and expanded under accredited facilities using good manufacturing practice standards. Potency assays are employed to confirm the cells retain their intended functional properties, such as cytokine secretion profiles or the ability to modulate immune cells. Sterility and mycoplasma testing guard against contamination, while identity tests verify that the correct cell type has been manufactured. Cryopreservation and controlled thawing are used to maintain viability for practical use, with careful documentation of donor or patient origin and processing history. The end product is released only when it meets predefined specifications, and post treatment follow up monitors for long term safety and effectiveness, recognizing that batch to batch variability can occur even within the same clinical program.

The science behind common misconceptions

One widespread belief is that stem cells simply replace damaged tissue in a one for one fashion. In reality, the biology is more nuanced. Engraftment rates of transplanted cells are often low, and persistent cell presence may be unnecessary for therapeutic benefit. Another misconception is that any stem cell will become any needed tissue freely; in practice, the microenvironment and intrinsic differentiation potential limit what a given cell population can achieve. Some clinics promote grandiose claims about curing complex diseases with a single infusion, but rigorous evidence typically shows benefits in specific contexts and often only when stem cell therapy is integrated with comprehensive medical care. Understanding the distinction between plausible mechanisms and overstated promises is essential for clinicians, researchers, and patients alike.

Future directions and ongoing research

The horizon of stem cell therapy is expanding as scientists explore ways to enhance safety, predictability, and efficacy. Gene editing technologies offer opportunities to correct disease related mutations in patient derived cells before implantation, while 3D bioprinting paves the path toward constructing tissue constructs with defined architecture. Secretome engineering aims to optimize the therapeutic cocktails that stem cells release, and extracellular vesicle based approaches pursue cell free therapies that maintain beneficial paracrine signaling without the risks associated with live cells. Researchers are also investigating combinations of stem cells with biomaterials, wound dressings, and pharmacological agents to create synergistic effects. This evolving landscape promises more precise patient stratification and improved outcomes as our understanding of cellular crosstalk deepens and manufacturing science advances further.

Real-world applicability and decision making

For patients considering stem cell therapy, realistic decision making rests on a careful appraisal of the evidence level for the specific condition, the stage of disease, and the availability of proven interventions. It is important to distinguish between therapies supported by high quality randomized trials and those still primarily investigated in early stage studies. Access and affordability matter, as do the credentials of the treating center, the specifics of the cellular product, and the proposed route of administration. Patients should engage in open conversations with clinicians about expected timelines, potential risks, and measurable endpoints that will indicate meaningful progress. A thoughtful plan will align the therapy with standard treatments, rehabilitation, and lifestyle modifications that collectively contribute to healthier outcomes. Ongoing participation in clinical trials, when appropriate, can also help expand the evidence base while ensuring careful patient monitoring and data collection for future patients.