What gallstones are and why symptoms vary

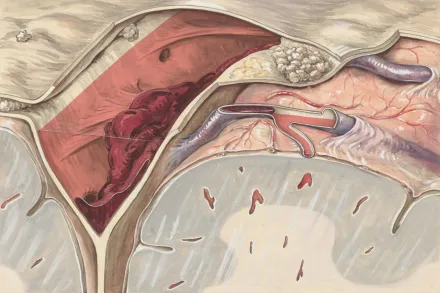

In human anatomy the gallbladder is a small pear shaped sac tucked beneath the liver that stores bile, a digestive fluid produced by the liver. Gallstones are hardened deposits that can form from cholesterol, pigment, or a mixture of substances within the bile. Some people harbor these stones for years without noticing them, while others experience repeated discomfort or acute episodes that send them to seek medical care. The reason symptoms vary so widely is that stones can travel into small ducts or become lodged in the cystic duct, triggering contraction of the gallbladder and a cascade of sensations that may differ from person to person. This variability makes it essential to recognize patterns, because the absence of pain does not always mean there is no stone, and the emergence of symptoms can be a signal that medical assessment is warranted.

Recognizing biliary colic and typical pain patterns

One of the most common presentations of symptomatic gallstones is biliary colic, a type of pain linked to the gallbladder’s attempt to move or push a stone along a duct. The pain is typically intense, sudden, and may begin in the upper right portion of the abdomen or just below the rib cage. It often lasts from twenty minutes to several hours and tends to ebb only when the stone shifts away or when the gallbladder relaxes. In many cases the pain radiates to the back between the shoulder blades or to the right shoulder, creating a spreading discomfort that can make it hard to find a comfortable position. The timing of episodes may correlate with meals, especially fatty meals, because these foods stimulate the gallbladder to contract in an effort to digest fat.

Where pain is felt and how it might spread

Pain related to gallstones most often centers in the upper right abdomen, but it can also appear in the epigastric region near the middle of the abdomen, or radiate to the back or right shoulder blade. Some people report a sense of pressure that feels more like fullness or squeezing than sharp stabbing pain. The distribution of pain is not always predictable; for instance a person with a stone near the duct opening may experience more diffuse discomfort across the midsection, while another person may feel concentrated tenderness in a very localized area. Understanding these patterns helps distinguish gallstone related discomfort from other abdominal or chest conditions, but it is important to consider associated symptoms and the overall clinical picture when interpreting the experience of pain.

Associated gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms

Beyond pain, several symptoms may accompany gallstones, reflecting how they interact with digestion and biliary drainage. Nausea and vomiting are common during an episode, and many individuals notice increased bloating, belching, or a sense of fullness after meals. Indigestion or an intolerance to fatty foods can occur, making meals feel heavy or uncomfortable. Some people experience a sour taste in the mouth or a temporary decrease in appetite. These associated symptoms can be mild or more pronounced, and they may fluctuate between episodes, reinforcing the idea that gallstones can cause intermittent discomfort rather than constant pain.

Warning signs that suggest complications require urgent care

While many gallstone episodes resolve on their own, certain signs indicate potential complications that require prompt medical attention. A fever, marked tenderness in the abdomen, or persistent vomiting can signal an inflammatory process such as cholecystitis. Jaundice, which manifests as yellowing of the skin or eyes, dark colored urine, or pale stools, may indicate obstruction of the bile ducts and requires urgent evaluation. Severe, continuous abdominal pain with fainting, confusion, or dehydration is a medical emergency. If any of these signs appear, seeking immediate care is crucial to prevent progression to more serious conditions.

Pain after meals: the fatty meal connection

The connection between fatty meals and gallstone symptoms is well documented. Fatty foods stimulate the gallbladder to contract to release bile for digestion, and if a stone blocks a duct this contraction can trap bile and intensify pain. People often notice that episodes occur after dining out, during large meals, or following a rich, heavy, or fried meal. This timing pattern helps distinguish biliary pain from other digestive issues that may be more steady or unrelated to meals. Even without frequent episodes, a documented pattern of postprandial pain should prompt discussion with a clinician, especially if the pain lasts for more than a short period or recurs repeatedly.

Differences between gallstone symptoms and other abdominal conditions

Several abdominal conditions can mimic gallstone symptoms, which is why a careful assessment is essential. For instance, pancreatitis often presents with upper abdominal pain that radiates to the back and is accompanied by nausea; however, pancreatitis may also involve elevated pancreatic enzymes and distinct laboratory findings. Peptic ulcers and gastritis can produce upper abdominal discomfort that worsens with meals or at night. Heartburn or esophageal reflux can feel chestward and sometimes confused with gallbladder pain. Kidney stones may cause intense flank pain that can migrate toward the groin. While these conditions share some features, the onset, location, radiation, associated symptoms, and triggers can help differentiate them, and a clinician can use this information to guide investigations such as imaging and blood tests.

Non-pain symptoms that may accompany gallstones

Not all gallstone related issues present with sharp abdominal pain. Some individuals experience mild, persistent discomfort in the upper abdomen or back that is easy to overlook, especially if it does not disrupt daily activities. Others report a sense of fullness after meals, mild nausea, or a temporary decrease in appetite during episodes. It is also possible to feel anxious, fatigued, or generally unwell during an episode, even when pain intensity is moderate. These non-pain symptoms can contribute to a slower recognition of gallstone involvement, particularly in people who have a high pain threshold or who attribute symptoms to simple indigestion or stress.

How clinicians assess suspected gallstones

When a patient presents with symptoms compatible with gallstones, clinicians begin with a detailed history focusing on the pattern of pain, triggers, and associated symptoms, followed by a physical examination. A clinician checks for tenderness in the right upper quadrant, looks for guarding or signs that suggest inflammation, and may perform maneuvers to elicit signs of gallbladder involvement. The assessment often includes evaluating for jaundice, fever, or signs of dehydration. The goal is to decide whether imaging and laboratory testing are warranted and to determine whether symptoms are more likely due to gallstones or another condition that requires a different treatment approach.

Imaging and tests: ultrasound and beyond

Ultrasound of the abdomen is the commonly preferred initial test for suspected gallstones because it can visualize the gallbladder and ducts without radiation and with high sensitivity for stones in the gallbladder. Ultrasound can also reveal signs of inflammation in the gallbladder, gallbladder wall thickening, or sludge that may contribute to symptoms. If ultrasound is inconclusive or if complications are suspected, additional imaging may be employed. Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography can provide detailed views of the biliary tree, while computed tomography may be used in certain scenarios to evaluate surrounding organs. In some cases, procedures that involve endoscopy, like endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, are necessary to assess or treat blockages within the bile ducts.

Laboratory tests and what the results mean

Blood tests are often used to complement imaging by checking indicators of liver function and inflammation. Liver function tests may show elevated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, or transaminases if bile flow is impeded or if there is inflammation in the biliary system. A complete blood count can reveal leukocytosis in the setting of infection or inflammation. Amylase and lipase levels may be checked to rule out pancreatitis if the pain pattern includes epigastric radiation to the back. Although many patients with gallstones have normal laboratory results during asymptomatic periods, abnormalities can appear during episodes and help guide management decisions and the urgency of intervention.

When symptoms are mild: asymptomatic gallstones

Not all gallstones produce symptoms. In fact, a substantial portion of people harbor stones that remain unnoticed until an imaging test performed for another reason reveals them. These asymptomatic stones do not always require immediate treatment, and many clinicians advocate a watchful waiting approach unless the stones begin to cause recurrent symptoms or complications. The decision to intervene depends on several factors, including the frequency of symptoms, stone size and location, the patient’s overall health, and potential risks associated with surgery. Regular follow up with a healthcare provider helps ensure timely action if symptoms evolve into a more troublesome pattern.

Risk factors that raise the likelihood of gallstones

Several factors increase the risk of developing gallstones. Age typically rises with risk, and women are more commonly affected than men, especially during reproductive years due to hormonal influences. Obesity and rapid weight loss contribute to imbalances in cholesterol in bile, promoting stone formation. A sedentary lifestyle, high-fat diets, and certain ethnic backgrounds also correlate with higher risk. A family history of gallstones can indicate a genetic susceptibility. Pregnancy temporarily increases risk because estrogen can influence cholesterol levels and gallbladder function. Understanding these risk factors helps individuals and clinicians consider an appropriate screening or monitoring strategy, particularly for those who present with compatible symptoms.

Gallstones in special populations: pregnancy and elderly

Pregnant individuals may experience gallbladder symptoms due to hormonal changes that slow gallbladder emptying and increase cholesterol saturation in bile. Symptoms during pregnancy require careful assessment to distinguish gallstone activity from other pregnancy related discomforts and to avoid unnecessary interventions unless needed. In elderly patients, symptoms may be milder or nonspecific, and comorbidities can obscure a classic presentation. A high index of suspicion is important in these groups, and clinicians may rely more on imaging and careful monitoring to avoid delayed diagnosis while ensuring safety for both mother and baby or for older adults with complex medical histories.

What to do if you have symptoms now

If you notice symptoms consistent with biliary colic or gallstone related discomfort, it is reasonable to start by noting the pattern, duration, intensity, and any triggering meals. Seek medical care if the pain is severe, persistent beyond a few hours, or accompanied by fever, persistent vomiting, or jaundice. Early evaluation helps determine whether imaging and laboratory tests are needed and may prevent complications. Until you can be seen, consider resting, avoiding heavy or fatty meals, staying hydrated, and avoiding self treatment that could mask symptoms or delay diagnosis. Clear communication with your healthcare provider about your history and current symptoms improves the accuracy of assessment.

Managing pain and comfort at home while awaiting evaluation

Home management focuses on comfort and safety while you arrange for medical assessment. Applying a warm compress to the upper abdomen can help relax the abdominal muscles and may ease discomfort, though heat should be used cautiously if fever is present. Gentle movement and light activities may reduce tension, yet intense activity should be avoided during a painful episode. It is important to maintain hydration and to monitor symptoms closely; if pain worsens, if you develop a high fever, or if you notice signs of dehydration such as dry mouth or reduced urine output, seek urgent medical care. Do not ignore new or escalating symptoms that could signal a complication requiring prompt intervention.

Lifestyle and dietary considerations to support gallstone symptoms

Dietary choices can influence the frequency and intensity of gallstone related symptoms. A plan that emphasizes smaller, more frequent meals with a moderate amount of healthy fats can help some individuals avoid large gallbladder contractions. Emphasis on fiber rich foods, vegetables, and whole grains supports digestion and may reduce bloating after meals. It can be helpful to limit highly fatty, fried, or processed foods, especially during symptomatic periods. Maintaining a healthy weight gradually and avoiding rapid weight loss also lowers the risk of stone formation. For some people, individualized dietary guidance from a healthcare professional provides the best balance between enjoyment, nutrition, and symptom control.

Next steps: monitoring, treatment options, and prevention

When symptoms are unmistakably linked to gallstones, treatment decisions depend on the severity and frequency of episodes, overall health, and potential complications. For those with recurring biliary colic or gallbladder inflammation, surgical removal of the gallbladder, a procedure known as cholecystectomy, is a common and effective option that can significantly reduce or eliminate symptoms. In some cases, less invasive interventions aimed at addressing bile duct stones, such as endoscopic procedures, may be considered. Ongoing monitoring, lifestyle adjustments, and timely medical follow up are important to prevent future episodes and to identify early signs of complications should they arise. A collaborative plan between patient and clinician guides safe, effective management that aligns with individual health goals and circumstances.