What constitutes a liver infection

A liver infection refers to inflammation of the liver tissue that arises because invading microorganisms disrupt the normal functioning of hepatic cells and the immune landscape within the organ. These infections can be caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, and occasionally fungi, each with its own pattern of spread and its own signature in laboratory tests and imaging studies. When the liver is invaded by a pathogen, the organ responds with immune activity that may be visible as fever, fatigue, or changes in the way the body metabolizes nutrients and toxins. The result is a spectrum that ranges from mild, transient inflammation to more pronounced disease that requires medical management. Understanding what constitutes a liver infection helps distinguish it from noninfectious liver disorders that can mimic symptoms in the early stages.

In practical terms, recognizing a liver infection starts with noticing symptoms that emerge or worsen after exposure to an infectious agent or after travel, street food consumption, or contact with contaminated water or bodily fluids. The liver’s role as a central metabolic hub means that infection can produce diffuse systemic signs, yet it also manifests through localized discomfort in the upper right portion of the abdomen. A liver infection does not always present with dramatic signs at first; some people experience subtle changes in energy, appetite, or skin tone before more overt symptoms appear. This variability makes awareness and medical evaluation crucial when symptoms persist or escalate.

Common early signs and symptoms

Early signs of a liver infection can blend with symptoms experienced during many illnesses, which is why an attentive approach matters. Fatigue or a lingering sense of weakness often accompanies a viral or bacterial challenge to the liver, and this fatigue may persist for days or weeks. Loss of appetite, nausea, and mild abdominal discomfort are frequently reported, sometimes accompanied by a feeling of fullness after small meals. Inflammatory processes can also trigger mild fever or night sweats, and this combination of systemic and local symptoms may prompt individuals to seek medical input. The body’s response to infection can also disrupt digestion, leading to occasional diarrhea or soft stools and a general sense of unsettled digestion.

As the infection progresses, other features may emerge. People might notice tenderness or aching in the upper right side of the abdomen where the liver sits beneath the rib cage, and this discomfort can be sharp after meals or physical activity. In some cases, the skin and whites of the eyes take on a yellowish tint, a sign that the liver’s ability to process bilirubin is affected. It is important to recognize that not every liver infection produces jaundice, but when jaundice appears along with dark urine or pale stools, it strongly suggests changes in how the liver handles bile pigments. The combination of symptoms can guide a clinician toward testing and closer observation.

Jaundice and changes in urine and stool

Jaundice arises when bilirubin, a yellow pigment produced during the breakdown of red blood cells, accumulates in the blood because the liver is not processing it efficiently. In the context of a liver infection, jaundice can reflect the liver’s struggle to conjugate and excrete bilirubin in a timely way. The visible signs—yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes—often appear gradually but can intensify over days. Some individuals may first notice a darker color to their urine, which occurs as bilirubin spills into the urine rather than being excreted in the stool. Conversely, pale or clay-colored stools can signal reduced bile flow into the intestines, another consequence of hepatic inflammation and obstruction.

These changes in urine and stool are not exclusive to liver infections and can occur with other liver disorders, but in combination with fatigue, fever, and abdominal discomfort, they raise concern for an inflammatory or infectious process in the liver. When jaundice is observed, it is essential to seek medical evaluation promptly, because timely assessment can help identify the underlying cause and determine the appropriate course of treatment. The medical team may order laboratory tests that measure bilirubin levels, liver enzymes, and other markers of liver function to clarify the picture.

When signs indicate a more serious issue

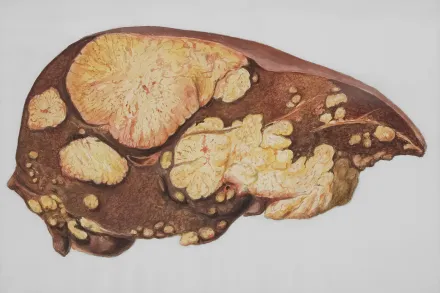

While many liver infections are mild and resolve with supportive care, some presentations signal a more serious condition that requires urgent medical evaluation. High fever that does not subside, severe and persistent right upper quadrant pain, confusion or marked changes in mental status, persistent vomiting or dehydration, and a rapid heartbeat are red flags that should prompt immediate medical attention. In certain infections, such as those caused by bacteria that form abscesses in the liver or by viruses that cause widespread inflammation, the clinical course can change quickly, leading to complications that affect the liver’s ability to function and the body’s overall balance. Recognizing these warning signs is essential because early intervention can prevent deterioration and improve outcomes.

In addition to subjective symptoms, objective signs such as abdominal tenderness on examination, signs of fluid buildup in the abdomen in advanced cases, or laboratory findings indicating elevated enzymes and bilirubin can help clinicians gauge the severity of illness. The goal of recognizing these indicators is to determine whether outpatient care is appropriate or whether hospitalization is necessary for close monitoring, intravenous therapy, and access to diagnostic imaging.

Causes and how infections reach the liver

Infectious processes that involve the liver include a variety of pathogens with distinct routes of entry and tissue effects. Viral hepatitis, caused by hepatotropic viruses, is among the most common conditions that focus attention on the liver and can be transmitted through blood, sexual contact, contaminated food or water, or close contact with an infected person. Bacterial infections can spread to the liver via the bloodstream, through neighboring organs, or from localized infections such as a biliary tract infection that drains into the liver. Parasitic infections add another dimension, often arising from exposure to contaminated water or undercooked foods in certain regions. Each category has its own signature pattern of symptoms, lab findings, and responses to therapy, which is why precise identification matters for prognosis and treatment.

The liver’s central location and its role in filtering blood mean that infections can provoke systemic symptoms as the immune system mobilizes a defense. In some cases, the infection remains localized in the liver, while in others it may spread or trigger inflammatory processes that affect nearby organs and bile ducts. Understanding the potential pathways for infection helps clinicians build a differential diagnosis so that testing can be targeted, and it helps individuals appreciate why staying connected with medical care is important when signs of illness emerge in the abdominal region or in the context of systemic symptoms.

Who is at risk and how to reduce risk

Risk factors for liver infections are diverse and include exposure histories, vaccination status, and preexisting health conditions. People traveling to areas with higher prevalence of hepatitis, travelers who dine on street foods or consume water from uncertain sources, and individuals who have had high-risk exposures may face increased risk. People with chronic liver disease, weakened immune systems, or those who use intravenous drugs can also be more susceptible to infections that involve the liver. Vaccination against hepatitis A and B provides strong protection, while other hepatitis strains lack vaccines or are prevented through safe practices and harm-reduction strategies.

Additionally, avoiding risky behaviors such as sharing needles, practicing safe sex, and ensuring precautions when handling blood or body fluids can reduce infection risk. Safe food and water practices, particularly when traveling, help minimize exposure to pathogens that commonly affect the liver. Routine screening for viral hepatitis in at-risk populations allows early detection and prompt treatment, which can reduce complications and transmission to others. Taking a proactive approach to liver health includes staying up to date on vaccines, seeking medical advice when symptoms arise, and following medical guidance about testing and treatment.

How clinicians diagnose liver infection

The diagnostic process for suspected liver infection blends history, physical examination, laboratory testing, and imaging. A clinician will inquire about recent travel, exposure to illnesses, vaccination status, and any signs of systemic infection, while a physical exam may reveal tenderness in the right upper quadrant or signs of liver disease such as jaundice. Blood tests measure liver enzymes, bilirubin, and markers of inflammation, and they may reveal patterns that point toward viral hepatitis or bacterial involvement. Serology panels can identify specific viruses, while blood cultures might be used when a bacterial infection is suspected. In some cases, stool tests or urine tests contribute to the overall picture.

When imaging is indicated, modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging help visualize the liver’s structure, detect abscesses, masses, or biliary obstruction, and assess the extent of inflammation. In certain situations a liver biopsy may be considered to obtain tissue for direct examination and to determine the exact cause of inflammation. The goal of diagnosis is to identify the specific infectious agent, assess the severity of liver involvement, and guide appropriate treatment, while also screening for potential complications that require additional care.

Treatment options and prognosis

Treatment for a liver infection depends on the identified cause, the severity of illness, and the individual’s overall health. Viral infections such as hepatitis viruses often rely on specific antiviral medications, supportive care, and close monitoring, since many forms of viral hepatitis do not respond to antibiotics. Bacterial infections may require targeted antibiotics and, in some cases, procedures to drain abscesses or address biliary obstruction. Parasite-related liver infections might involve antiparasitic therapies, sometimes combined with supportive measures to alleviate symptoms and maintain hydration and nutrition. Across etiologies, maintaining comfort, ensuring adequate rest, and managing pain are common components of care, while monitoring for potential complications is ongoing.

Prognosis varies widely. Mild viral hepatitis can resolve with minimal intervention, especially when detected early and managed with rest and hydration. More complex infections or those in people with additional health issues, such as preexisting liver disease or immune suppression, may require longer treatment and carry higher risk of complications. Prompt medical evaluation improves the chances of a favorable outcome by enabling timely treatment, reducing the risk of progression, and protecting liver function. Even after recovery, some individuals may require follow-up testing to confirm that liver enzymes have returned to normal and to ensure that there is no ongoing inflammation.

Prevention strategies

Prevention of liver infections centers on vaccination where available, safe practices, and attention to environmental exposures. Vaccines for hepatitis A and hepatitis B play a crucial role in reducing the burden of infection and its consequences, especially for travelers, healthcare workers, and people at higher risk of exposure. Safe handling of food and water, particularly in regions with uncertain sanitation, helps minimize the risk of ingesting viruses and bacteria that target the liver. When possible, avoiding exposure to contaminated blood or bodily fluids and using protective measures in sexual activity contribute to prevention. Practicing good hygiene, including regular handwashing and avoiding sharing personal items that may come into contact with blood, supports liver health by limiting the spread of infectious agents.

In addition to vaccination and hygiene, early medical evaluation for symptoms such as persistent fatigue, abdominal discomfort, or changes in urine and stool can facilitate early detection and reduce the likelihood of complications. People with a history of liver disease or immune-related conditions should have conversations with their healthcare providers about appropriate screening, vaccination, and preventive strategies. While some infections have no vaccine, comprehensive prevention still rests on minimizing exposure, seeking timely care, and adhering to treatment recommendations when infection is suspected or confirmed.

Living with liver infection: practical considerations

Living with a liver infection entails a combination of rest, nutrition, hydration, and careful attention to how the body responds to infection. Adequate rest supports the immune system as it works to clear the infection, and balanced meals that emphasize gentle, nutrient-dense foods can aid recovery. Hydration helps maintain blood flow and supports liver function during illness, while avoiding alcohol and hepatotoxic substances reduces additional stress on the liver. Individuals who notice persistent symptoms, worsening pain, or new concerns should seek medical help promptly, because timely evaluation can adjust treatment and prevent complications.

Communication with healthcare providers is essential for tailoring care to the specific infection. Patients may be advised to monitor symptoms at home, maintain a record of fever episodes, medication use, and any changes in appetite or energy, and follow-up testing may be arranged to ensure that the liver is returning to its normal state. In cases where vaccination is indicated, completing the vaccine series according to a clinician’s guidance contributes to longer-term protection. Adopting a supportive mindset, adhering to prescribed therapies, and remaining vigilant for warning signs collectively empower individuals to navigate liver infections with greater confidence and clarity.