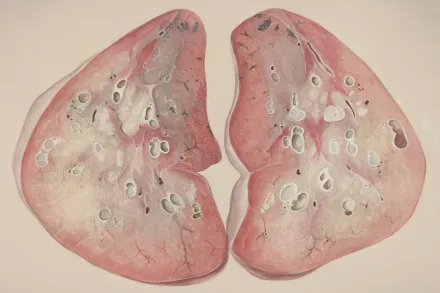

The liver is a remarkable organ that performs hundreds of crucial tasks essential to maintaining the body’s internal balance. It detoxifies, metabolizes nutrients, produces bile for digestion, stores vitamins and minerals, helps regulate hormones, and supports the immune system. Because the liver works behind the scenes and can compensate when injury or illness begins, symptoms may be subtle at first. Recognizing signs of liver disease in its early stages can open a window for timely medical assessment and intervention, potentially preventing progression to more serious conditions. This article explores the signals that may indicate liver trouble, explains why these signs appear, and outlines practical steps for individuals to take when they notice something unusual. Understanding these cues requires a holistic view of health because liver disease often intersects with dietary habits, alcohol use, metabolic conditions, genetic predispositions, infections, and environmental exposures. The goal is not to induce fear but to promote awareness, encouraging people to seek professional evaluation when persistent changes occur, rather than assuming they will resolve on their own. Early detection can improve outcomes and preserve quality of life by enabling appropriate diagnosis, lifestyle adjustments, and targeted treatment if needed.

The liver’s role in processing toxins means that early disease may reflect a buildup of substances that the liver could not manage efficiently. When signs emerge, they may touch multiple systems rather than presenting as a single symptom. Some early indicators might be easily attributed to fatigue, stress, or a transient viral illness, which is why awareness matters. A patient may notice that simple activities become tiresome, that meals produce uncharacteristic discomfort, or that skin and eyes appear subtly altered. Because liver disease can be dynamic, fluctuating with hydration, weight, and infection status, keeping a careful record of symptoms and timing helps clinicians distinguish normal bodily variation from something requiring evaluation. Medical professionals often emphasize that any persistent or worsening symptom across weeks warrants careful assessment, and this approach is true even for individuals who otherwise feel healthy. The following sections outline the signs that commonly occur in the early course of liver disease, how they relate to underlying processes in the liver, and what steps to take if they appear. By connecting physical cues with medical evaluation, people gain a practical path to safeguarding liver health without unnecessary alarm.

Early signs of liver disease may arise gradually as the organ’s capacity to metabolize fats, sugars, and toxins becomes impaired. In some people, subtle changes in appetite or energy may be the first clue, long before more dramatic symptoms arise. The pathophysiology behind these signs can involve inflammation, scarring, fatty infiltration, or impaired bile production, each with its own implications for treatment. For example, inflammation can respond to medical therapy or lifestyle modifications, while scarring signals a chronic process that may require ongoing management to slow progression. Understanding that early signs are not random but connected to how the liver functions can empower individuals to seek timely guidance. It is also important to recognize that liver disease can be silent for extended periods in some people, especially those who do not have obvious risk factors. This reality reinforces the value of routine health checks, especially for people with risk factors or a family history of liver disorders. The aim of early detection is not merely to diagnose but to begin a constructive path toward prevention, monitoring, and, if needed, treatment that aligns with a person’s overall health goals.

Among the most useful strategies for catching liver disease early is routine conversation with healthcare providers about any persistent changes. This includes asking about the potential impact of medications, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements, which can influence liver function. It is equally important to discuss lifestyle factors such as alcohol use, weight management, and metabolic health, all of which can affect the liver. A clinician may recommend baseline blood tests, imaging studies, or screening for specific conditions depending on an individual’s symptoms and risk profile. While many liver conditions share overlapping signals, careful history taking and focused testing can differentiate among fatty liver disease, viral hepatitis, autoimmune processes, and less common conditions. Early engagement with a clinician also offers an opportunity to receive guidance on nutrition, physical activity, sleep, and stress management, all of which can support liver health even before a formal diagnosis is made. The overarching message is clear: early recognition paired with proactive medical engagement can transform the trajectory of liver disease for many people.

Understanding the liver and why early detection matters

The liver, perched high in the abdomen just beneath the rib cage on the right side, carries out a broad spectrum of tasks that sustain metabolic stability and detoxification. Its remarkable regenerative potential allows the organ to recover from certain insults when identified promptly and addressed with appropriate care. However, when liver disease progresses, the consequences can extend beyond localized tissue damage to systemic effects that involve the circulatory, nervous, and immune systems. Early detection is often linked to simpler, more effective interventions, including weight management, dietary adjustments, alcohol moderation, control of viral infections, and modification of medications that may harm liver tissue. The sooner a problem is detected, the more options clinicians have to minimize disease progression and improve long-term outcomes. This is particularly important in conditions such as fatty liver disease, early cirrhosis, or autoimmune hepatitis, where timely treatment can halt or reverse some of the damage and prevent complications like portal hypertension or liver failure. Recent advances in noninvasive testing further empower clinicians to identify changes in liver tissue without invasive procedures, making early screening more accessible for many patients. The cumulative impact of early detection includes preserving liver function, reducing hospitalizations, and supporting a person’s ability to pursue a full and active life. This broader perspective helps patients understand why symptoms matter not only as signals of discomfort but as actionable information guiding medical care.

As with many organs, liver health exists on a spectrum, with individuals experiencing varying degrees of resilience. Some people may notice minor adjustments in energy or digestion that do not progress, while others may develop more pronounced signs that require urgent attention. Education about risk factors can also play a critical role in prevention. For example, excess body weight, insulin resistance, and high triglycerides are commonly linked to fatty liver disease, while certain medications, alcohol use, and viral infections can initiate inflammatory responses within hepatic tissue. Knowledge of these associations encourages proactive steps that may prevent disease or slow its course. It also helps people interpret symptoms more accurately, so they know when to seek medical advice. By combining self-awareness with regular medical checkups, individuals give themselves a greater chance of maintaining liver health over time. This approach reflects a practical philosophy: treat early signs as potential warnings rather than as isolated incidents, inviting professional assessment to reveal underlying mechanisms that may be addressed with targeted interventions.

Common early signs you should not ignore

Fatigue is a non-specific but frequently reported symptom that can accompany many conditions, including mild infections and sleep disturbances. When fatigue becomes persistent or disproportionately intense relative to daily activities, it may indicate a metabolic issue involving the liver, especially if it coincides with other changes in the body. In liver disease, fatigue can reflect altered energy production, impaired detoxification processes, or hormonal imbalances that influence energy levels. Another prominent signal is discomfort or a sense of fullness in the upper right abdomen, where the liver sits. This sensation may be dull or sharp and can be mistaken for muscle strain or gas, but persistent abdominal discomfort in this area deserves attention because it may relate to hepatic inflammation or enlargement. Appetite changes are common as the liver’s involvement in nutrient processing shifts. Some individuals experience reduced appetite or early satiety, whereas others may crave foods they do not typically favor. Weight fluctuations that are unexplained or disproportionate to activity levels also warrant scrutiny, since liver disease can influence metabolism and fluid balance in ways that alter body weight. Nausea and episodes of vomiting can accompany liver dysfunction, particularly when there is bile flow disruption or immune-mediated inflammation. Although these symptoms are nonspecific, their persistence alongside other signs increases the likelihood of a hepatic contribution to the clinical picture. It is essential to consider the full constellation of symptoms rather than focusing on a single complaint, because multiple signs appearing together strengthen the case for a liver-related explanation. When fatigue, abdominal discomfort, appetite changes, weight variation, and nausea recur over weeks, a clinician will often begin a structured evaluation to determine whether liver health plays a role. This careful approach recognizes that early liver disease can masquerade as more common, benign conditions, underscoring the importance of vigilance and professional assessment.

Itching, or pruritus, is another symptom that can accompany liver disease. The itch is often generalized and not explained by skin dryness or dermatologic conditions. Bile acids that accumulate due to impaired liver processing can irritate nerve endings in the skin, producing a persistent urge to scratch. In the early stages, itching may be mild and intermittent, but it can become a significant quality-of-life issue if the underlying liver problem progresses. Jaundice, characterized by a yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes, can develop as bilirubin builds up in the bloodstream when liver function declines. The appearance of yellowing may begin in the sclera of the eyes and later extend to the skin, lips, and nails. Jaundice is particularly concerning when it occurs alongside dark urine and pale stools, as these color changes often reflect altered bilirubin metabolism and excretion. Dark urine results from concentrated pigment in the urine, while pale stools indicate reduced bilirubin reaching the intestine for color transformation. The presence of jaundice warrants prompt medical evaluation, especially if accompanied by abdominal pain, swelling, or confusion, as it can signal progressive liver disease or bile duct obstruction. Other early signs may include swelling of the legs or abdomen due to fluid retention, a phenomenon known as edema, which may point to cirrhosis or portal hypertension in more advanced scenarios. These signs together form a clinically meaningful pattern that clinicians recognize as potential liver disease and respond to with targeted testing, imaging, and therapeutic planning. The comprehensive approach ensures that subtle cues are not overlooked and that patients receive timely guidance about next steps and potential treatment options.

Beyond these common signals, some people experience changes in skin coloration, including a yellowish tint in the eyes or skin that is not caused by sun exposure. This is typically a more obvious manifestation of bilirubin processing issues and may occur alongside other metabolic signs. Another important clue is the appearance of venous patterns in skin that resemble spider webs, particularly on the chest and shoulders, which can reflect underlying vascular changes linked to liver disease. Palmar erythema, a reddening of the palms, can also occur due to shifts in sex hormones and other compounds processed by the liver. While these skin changes are not exclusive to liver disease, their presence, especially when combined with fatigue, abdominal symptoms, or jaundice, should raise concern and prompt evaluation by a clinician. The older medical literature sometimes described these findings as late signs, but contemporary practice recognizes that some patients may experience skin manifestations early in the disease course. Clinicians will weigh these signs in the broader clinical context, considering age, sex, body habitus, coexisting conditions, medications, and exposure history to determine the pretest probability of liver involvement and to plan appropriate testing. This comprehensive assessment is crucial because many skin and systemic signs are nonspecific and can be influenced by a range of factors, including chronic skin conditions, allergies, or endocrinopathies. When there is any doubt, seeking medical advice ensures that the liver is considered as part of the differential diagnosis rather than being dismissed as incidental.

Why the liver may not cause obvious symptoms initially

Several illnesses of the liver begin quietly, with biochemical changes that precede overt symptoms. Liver cells can adapt to mild insults by increasing their functional efficiency or by compensating through parallel pathways. This adaptability may delay the appearance of noticeable signs, which means small abnormalities detected on routine blood tests can be the earliest breadcrumb trail pointing toward a problem. In many individuals, liver function tests may remain within normal ranges until a substantial portion of hepatic tissue is affected, creating a window during which disease can progress undetected. This phenomenon highlights the value of routine screening for people with risk factors or with family histories that predispose them to hepatic conditions. Regular blood work and imaging studies can identify abnormal patterns such as elevated liver enzymes, altered bilirubin, or changes in albumin levels that signal inflammation, damage, or impaired synthetic function, even before clinical symptoms surface. Early biochemical abnormalities provide an opportunity to investigate underlying etiologies, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, viral infections, autoimmune conditions, metabolic disorders, or exposure to hepatotoxins. Recognizing that the absence of symptoms does not guarantee the absence of disease is a practical reminder to maintain proactive health monitoring, especially for individuals with risk factors or ongoing exposures that can affect liver health. In this way, clinicians and patients work together to uncover subtle signals and translate them into timely diagnostic steps that preserve liver function and overall well-being.

It is also important to note that some people may experience intermittent symptoms that come and go, creating a pattern of fluctuations rather than a steady course. For instance, a person might notice episodes of mild discomfort after meals or periods of fatigue that resolve after a few days, only to recur weeks later. Such cycles can reflect transient inflammatory activity, variations in bile flow, or changes related to hydration and activity levels. This variability can be confusing for patients who hope that symptoms will disappear on their own, but it also offers a chance to catch shifting patterns that may reveal an evolving problem when tracked over time. Keeping a symptom diary that records the onset, duration, intensity, accompanying events, and any medications can be a valuable tool for clinicians who are assessing potential liver disease. It provides a narrative of the body’s responses to foods, medications, alcohol, infections, and stress, which helps specialists construct a clearer picture of what is happening inside the liver and how best to intervene. The idea is to cultivate mindfulness about bodily signals and to approach any persistent irregularity with careful medical inquiry rather than casual tolerance. This proactive stance supports earlier detection and more effective management, as professionals can correlate observed signs with laboratory results and imaging findings to arrive at a precise diagnosis.

Specific signs in the skin and eyes

Jaundice is the most widely recognized indicator of liver-related bilirubin handling problems, yet it is not the only signal that dermatologic and ocular changes can reveal. Subtle yellowing of the whites of the eyes may precede noticeable skin coloration, drawing attention to bilirubin dynamics and liver excretion pathways. In some individuals, the skin may acquire a yellowish tint in localized areas or more generalized pallor or a dull complexion as a reflection of metabolic shifts that accompany liver disease. Spider angiomas represent another skin sign that clinicians associate with hormonal and vascular changes occurring when the liver’s detoxification and synthetic capabilities are compromised. These tiny, red spider-like lesions commonly appear on the face, neck, chest, or shoulders and are more typical in certain liver conditions, particularly those associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Palmar erythema is the reddening of the palms, which can emerge with hormonal imbalances propagated by reduced processing of estrogen and other compounds in the liver. While these skin manifestations can arise from non-hepatic causes as well, their appearance alongside other signs such as fatigue, abdominal discomfort, or jaundice raises the likelihood of a hepatic contribution to the problem. People who notice these dermatologic changes should consider scheduling a medical evaluation, particularly if they are persistent, spreading, or accompanied by other symptoms. Timely assessment allows clinicians to determine whether dermatologic signs are a clue to an underlying liver process requiring treatment, lifestyle modification, or further investigation. In some cases, addressing the root liver condition can lead to improvement in the associated skin signs, illustrating how interconnected bodily systems are.

In the realm of ocular signs, beyond jaundice, patients may notice mild yellowing of the sclera or changes in the depth of eye coloration that reflect bilirubin processing challenges. The eyes can serve as an early window into hepatic function when bilirubin clearance becomes less efficient, signaling the need for a deeper diagnostic workup. Such signs may appear alongside dark urine or pale stools, which are consequences of changes in bile excretion and bilirubin metabolism. Colorful changes in urine and stool can alert patients and clinicians to look for liver- or bile duct-related etiologies that could benefit from imaging studies or liver function testing. It is important to emphasize that not all skin and eye color changes are cause for alarm, but when they occur with other symptoms or in a context of risk factors, they deserve careful evaluation. A measured, patient-centered approach that respects the person’s experiences and concerns helps guide the next steps toward a precise diagnosis and appropriate management. In this light, skin and eye signs should be interpreted as part of a broader clinical picture rather than as standalone diagnoses.

Digestive and abdominal symptoms to watch

Digestive symptoms frequently accompany liver disease, reflecting the organ’s central role in digesting and metabolizing fats and proteins. Some individuals may experience persistent bloating, gas, or fullness after meals that lasts longer than would be expected from typical dietary indiscretions. This sensation can occur when the liver’s bile production is insufficient to emulsify fats, slowing the process of digestion and leaving residual fats in the gut. Individuals might notice a change in stool consistency, such as lighter or clay-colored stools, which can indicate reduced bile flow into the intestine. Conversely, stools that appear unusually dark can be a signal of bilirubin processing issues. Nausea and vomiting can accompany hepatic inflammation or cholestasis, and these symptoms may be episodic or persistent depending on the underlying condition. The presence of upper abdominal pain, particularly if localized to the right upper quadrant where the liver resides, should prompt consideration of liver-related causes alongside other possibilities. Pain that worsens after meals or during episodes of dehydration can be a red flag for clinicians who monitor hepatic health. Abdominal swelling or distension due to fluid accumulation, known as ascites, represents a more advanced stage of liver disease but can manifest in subtle forms earlier in the disease course as well. Monitoring these digestive cues in combination with systemic signs provides a coherent framework for recognizing when liver health may be at risk. Proactive evaluation in the presence of persistent digestive symptoms can prevent misattribution to benign causes and ensure timely diagnosis and treatment.

Beyond local symptoms, systemic digestive changes such as persistent mild fatigue after meals, a tendency toward irritability, or cognitive fog can reflect hepatic involvement, particularly when they persist and are not explained by sleep, mood, or stress alone. The liver’s role in metabolizing toxins and producing essential proteins means that when its function is compromised, biochemical signals can ripple through the body, affecting digestion, energy, and mood. Recognizing these broader patterns helps avoid the pitfall of focusing on individual symptoms in isolation. When digestive symptoms co-occur with jaundice, itching, or weight changes, clinicians are more likely to pursue a hepatic-focused workup to differentiate liver disease from other gastrointestinal disorders. This approach underscores the importance of comprehensive assessment rather than a narrow focus on a single symptom. The goal is to identify a cohesive symptom cluster that points toward liver health concerns and to respond with appropriate testing and intervention.

Metabolic and systemic clues

Metabolic disturbances frequently accompany liver disease and can provide important early warning signs. Insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome raise the risk of fatty liver disease, a condition that is increasingly common worldwide due to rising rates of obesity and sedentary lifestyles. In these circumstances, one may observe weight gain around the abdomen, elevated fasting glucose levels, and abnormal lipid profiles such as high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol. While these findings can be present in individuals without liver disease, their coexistence with liver-specific signs strengthens the case for a hepatic evaluation. The liver’s involvement in producing albumin and clotting factors means that a decline in these proteins can manifest as swelling, easy bruising, or edema in the legs and abdomen. Persistent edema suggests that the liver is not maintaining the proper balance of fluid and proteins, signaling a more advanced stage that requires careful medical management. In addition, researchers have noted that certain autoimmune and genetic liver conditions can manifest with systemic symptoms such as fatigue, low-grade fevers, or malaise that do not directly involve the digestive tract. These clues remind clinicians to consider a broad differential diagnosis while maintaining a focus on hepatic causes when systemic signs appear alongside laboratory abnormalities. Understanding these metabolic and systemic cues allows for a more nuanced interpretation of patient presentations and supports timely, targeted testing to identify liver disease at an earlier stage.

Weight fluctuations that are unexplained by diet or exercise, changes in body composition, and shifts in energy levels can all reflect disturbances in hepatic metabolism. The liver coordinates many enzymatic reactions that process fats, carbohydrates, and proteins, and when its function is compromised, metabolic homeostasis can be disrupted. This disruption may present as difficulty losing weight despite adherence to a calorie-restricted plan, or conversely as unintended weight loss from systemic illness or malabsorption associated with liver disease. Clinicians often assess liver function in the context of broader metabolic health, recognizing that abnormalities in liver enzymes or bilirubin may correlate with insulin resistance, fatty infiltration, or inflammatory processes in the liver tissue. The interplay between metabolism and liver health means that a holistic evaluation of dietary patterns, physical activity, and metabolic laboratory markers is essential for accurate interpretation. By incorporating metabolic cues into the diagnostic process, healthcare providers can identify at-risk individuals earlier and tailor interventions to address both liver-specific disease and associated metabolic conditions.

Chronic fatigue and a general sense of reduced stamina can arise from the liver’s diminished capacity to detoxify and regulate energy-producing pathways. Patients often report that even routine tasks feel more exhausting, and beyond mere tiredness, they may experience a sense of cognitive sluggishness or mental fatigue. This cognitive aspect, sometimes referred to as hepatic encephalopathy in more advanced stages, can begin subtly and become more noticeable as liver function declines. Recognizing that these neuropsychological changes can have multifactorial origins, clinicians may explore the liver’s role when fatigue is persistent and accompanied by other signs such as altered handwriting, mood changes, or confusion. Early detection relies on careful history-taking and observation of symptom progression. When metabolic, fatigue-related, and neurocognitive cues converge with liver-specific indicators like jaundice or changes in stool and urine color, the likelihood of hepatic involvement becomes more compelling, guiding timely diagnostic workups and early interventions that can alter the disease’s trajectory.

Neurological and mental status changes

The liver’s failure to detoxify ammonia and other toxins can impact brain function, leading to a spectrum of neuropsychiatric symptoms. In earlier stages, subtle changes in concentration, memory, or clarity of thought might be present, especially after meals or during periods of stress. As liver disease advances, more pronounced symptoms such as confusion, sleep disturbances, mood swings, or impaired judgment can emerge. This progression can be confusing to patients and families who may misattribute cognitive changes to stress, aging, or sleep disorders. Early recognition of hepatic-related cognitive changes involves a careful assessment of timing, context, and associated signs. Clinicians may perform cognitive testing and review medications, nutrition, and toxin exposures to distinguish hepatic causes from primary neurological conditions. The recognition that liver health can influence mental status reinforces the importance of integrated care, in which hepatologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, and primary care providers collaborate to evaluate and treat complex presentations. For patients, discussing cognitive symptoms openly with a clinician, noting frequency and triggers, can accelerate diagnosis and appropriate management, including dietary changes, medication adjustments, and specialized therapies that support brain function while addressing liver health.

In addition to cognitive concerns, sleep disturbance can be an early signal of liver disease, as the liver’s role in toxin clearance and metabolic regulation intersects with circadian rhythms. People may experience difficulties falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up feeling unrefreshed. Although many people experience occasional sleep problems, persistent disruption that accompanies other signs should prompt a medical evaluation. Sleep-related symptoms can be influenced by sleep habits, stress, and mood disorders, yet when they occur alongside fatigue, jaundice, or digestive changes, they contribute to a broader pattern that clinicians interpret as possible hepatic involvement. Understanding this relationship helps patients discuss sleep concerns in the context of overall liver health, enabling clinicians to determine whether sleep issues reflect a liver-related mechanism or a separate orthopedic, psychiatric, or environmental factor. This integrated perspective supports a more precise diagnostic pathway and encourages early interventions that can improve both liver function and sleep quality, ultimately enhancing overall well-being.

Dedicated groups at risk and what that means for screening

Screening and risk assessment for liver disease depend on recognizing populations with higher likelihood of developing hepatic conditions. Individuals with obesity, type 2 diabetes, or metabolic syndrome carry a greater risk for fatty liver disease, sometimes without noticeable symptoms in the early stages. Likewise, chronic hepatitis B or C infections, autoimmune liver diseases, and genetic conditions such as hemochromatosis or Wilson’s disease establish a predisposition to liver injury. People who use excessive alcohol or have a history of significant alcohol use are at heightened risk for alcoholic liver disease and related complications. Exposure to hepatotoxic substances, including certain medications, supplements, and environmental toxins, also plays a role. When clinicians identify patients in higher risk groups, they may proactively recommend targeted testing, lifestyle interventions, and periodic imaging to monitor liver health. This approach aims to catch disease before it causes irreversible damage, emphasizing prevention alongside treatment. For individuals with known risk factors, conversations about liver health should be routine, integrating liver-focused questions into annual checkups and guiding decisions about screening frequency and the use of noninvasive tests. This proactive approach recognizes that risk stratification does not depend solely on symptoms but on a combination of medical history, family history, behavioral factors, and objective measurements. By prioritizing timely screening for at-risk groups, healthcare systems can identify early-stage disease and implement programs that reduce long-term consequences such as cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and liver failure.

Healthcare teams often discuss the importance of vaccinations and infection prevention for those at risk of liver disease due to viral hepatitis, as vaccines for hepatitis A and B can reduce the burden of liver-related illness. Individuals with risk factors are advised to engage in preventive care, including vaccination, safe sexual practices, avoidance of sharing needles, and cautious use of medications and supplements that may impact liver function. The goal is to empower patients to participate actively in their health care, asking questions, seeking information, and adhering to recommended screening schedules. This collaborative approach helps ensure that liver health remains a central consideration in overall wellness management. By acknowledging risk factors and pursuing appropriate screening, patients can take concrete steps that reduce the likelihood of advanced liver disease and improve long-term health outcomes.

What to do if you notice signs

When you notice persistent signs that could indicate liver trouble, the first step is to schedule a visit with a primary care clinician or a hepatology specialist. Bring a detailed description of symptoms, their onset, duration, any potential triggers, and a list of current medications, supplements, and over-the-counter products. A clinician will typically conduct a thorough physical examination and review risk factors such as alcohol consumption, weight trends, diabetes status, and family history. This information informs the diagnostic approach, which may include blood tests to assess liver enzymes, bilirubin levels, albumin, and clotting factors, as well as imaging studies like ultrasound or elastography to evaluate liver texture and blood flow. The results help determine whether liver disease is present and what kind of disease mechanism is at play. Depending on findings, additional tests for viral hepatitis, autoimmune conditions, iron and copper metabolism, and genetic disorders may be ordered. Early consultation with specialists can prevent delays in diagnosis and ensure that appropriate lifestyle and therapeutic strategies are pursued promptly, which can slow the disease’s progression and mitigate complications. If symptoms escalate rapidly or include severe abdominal pain, fever, confusion, or fainting, urgent care or emergency services should be sought, as these scenarios may signify acute liver failure or other critical conditions requiring immediate intervention.

Measures you can take alongside medical evaluation include maintaining a balanced, liver-friendly diet rich in fiber, vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats while limiting processed foods, added sugars, and saturated fats. Regular physical activity, adequate hydration, and sufficient sleep support metabolic health and liver function. If alcohol is part of your life, discussing safe limits with a clinician is essential, as alcohol can cause or worsen liver injury even in individuals without preexisting disease. Managing comorbid conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and high cholesterol is also a key component of preserving liver health. When medications are necessary, review them with a healthcare provider to ensure that drug choices, dosages, and combinations do not pose a risk to the liver. In some cases, clinicians may adjust medication regimens, substitute hepatotoxic agents, or monitor liver function more closely during treatment. The overarching strategy is to adopt a proactive, measured approach that respects liver biology, avoids unnecessary alarm, and prioritizes evidence-based actions that support recovery and maintenance of liver health over time.

What doctors may check and why tests matter

Initial laboratory testing usually includes a panel of liver function tests that measure enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase, as well as bilirubin and albumin levels. These tests help identify hepatocellular injury, cholestasis, or impaired synthetic function. A complete blood count provides information about anemia, infection, and platelet count, which can be affected by liver disease and portal hypertension. A coagulation profile assesses the blood’s ability to clot, a process that can be altered when the liver’s capacity to produce clotting factors declines. In addition to blood tests, imaging studies such as abdominal ultrasound or elastography enable visual assessment of liver size, texture, and the presence of fatty infiltration or scarring. Special tests may be indicated to diagnose viral hepatitis, autoimmune liver disease, metabolic disorders, or hereditary conditions. In some cases, a liver biopsy may be necessary to determine the specific disease type and stage, although noninvasive alternatives are increasingly used to avoid invasive procedures whenever possible. The combination of laboratory data and imaging results informs diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment decisions, guiding clinicians toward the most appropriate management plan for each patient. The diagnostic process is tailored to the individual, reflecting unique risk factors, symptom patterns, and medical histories, with the aim of achieving clarity and effective care.

Understanding the purpose of each test helps patients engage more confidently in the diagnostic journey. For example, elevated liver enzymes can indicate hepatocellular injury but can occur with a range of conditions from viral infection to medication toxicity. Bilirubin elevation points toward impaired processing or excretion; a low albumin level may reflect reduced synthetic capacity and correlate with disease severity. Imaging can reveal fatty changes in the liver, structural abnormalities, or signs of cirrhosis, while serologic tests can support the identification of immune-mediated etiologies or infectious causes. The results of these tests, interpreted within the context of symptoms and risk factors, help clinicians determine the seriousness of liver disease and set a course for management. A timely, comprehensive evaluation can lead to early treatment interventions, risk stratification, and ongoing monitoring that reduce the likelihood of complications and preserve liver function over time. In this way, tests become more than numbers; they are practical indicators guiding real-world care that can improve outcomes and offer reassurance when results are favorable. This collaborative process between patient and clinician forms the backbone of effective liver health management.

Lifestyle and risk reduction to protect liver health

Protecting liver health involves a combination of dietary choices, physical activity, moderation of alcohol intake, vaccination, safe handling of medications, and avoidance of toxins. Emphasizing a balanced diet rich in whole foods, vegetables, lean proteins, healthy fats, and complex carbohydrates supports liver function and metabolic stability. Limiting highly processed foods, refined carbohydrates, and added sugars reduces the metabolic strain on the liver and can help mitigate the progression of fatty liver disease. Regular physical activity, including both aerobic and resistance training, improves insulin sensitivity, reduces inflammation, and supports weight management, all of which contribute to healthier liver tissue. Avoiding excessive alcohol consumption is a cornerstone of liver preservation, and individuals who consume alcohol should do so within guidelines advised by their healthcare provider to minimize hepatic harm. Vaccinations against hepatitis A and B protect the liver from infectious injury and are recommended for individuals at risk or with exposure histories. Safe medication practices involve discussing all over-the-counter drugs, supplements, and prescription medications with a clinician to ensure that chosen therapies do not contribute to liver injury. Some substances, including certain herbal products and dietary supplements, can have hepatotoxic effects, and awareness of these risks supports safer use. Environmental and occupational exposures to toxins should be minimized, particularly for people who work with solvents, pesticides, or other chemical agents known to impact liver health. By integrating these lifestyle and preventive measures, individuals can reduce their risk for liver disease and improve overall well-being.

Weight management and dietary quality play critical roles in preventing and managing liver disease. Achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight reduces fat accumulation in the liver and lowers the risk of progression to more advanced disease states. Nutrition plans that focus on moderate portion sizes, high fiber intake, lean sources of protein, and a range of micronutrients support liver health without placing excessive metabolic demands on the body. Patients with metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes may benefit from working with nutritionists or dietitians to tailor plans that address both glycemic control and hepatic fat reduction. Regular check-ins allow adjustments to diet as liver function tests and metabolic markers evolve, ensuring that dietary choices remain aligned with the person’s health goals and clinical status. In addition, staying hydrated, prioritizing sleep, and managing stress have meaningful, albeit sometimes subtle, influences on liver health since these factors affect metabolism, inflammation, and recovery processes. This holistic approach to lifestyle ensures that liver protection becomes an integrated part of everyday living rather than a separate or punitive program.

When to seek urgent care

Urgent medical attention is warranted if signs of acute liver failure appear, including confusion, severe abdominal swelling, unusual sleepiness, fainting, or sudden, severe abdominal pain with signs of infection or bleeding. Rapid progression of jaundice, dark urine with pale stools, or persistent high fever accompanying abdominal tenderness can indicate a severe condition requiring emergency evaluation. Other red flags include noticeable swelling of the legs or abdomen that rapidly worsens, bleeding easily or bruising without trauma, and persistent vomiting that prevents adequate hydration. The appearance of such alarming symptoms does not mean a definitive diagnosis is certain, but it signals the necessity for timely medical assessment to identify potentially life-threatening conditions and to initiate urgent treatment when needed. In these situations, prompt care aims to stabilize the patient, manage complications, and determine the underlying cause so that appropriate interventions can be started without delay. If there is any doubt about the severity of symptoms or the risk of deterioration, seeking emergency care is the safest course of action.

For less acute concerns, but signs that persist or worsen over weeks, arranging an appointment with a healthcare provider is still essential. If fatigue, digestive changes, or skin signs persist after a reasonable period of rest and lifestyle adjustment, professional evaluation helps distinguish between liver-related disease and other conditions. Early, non-emergency consultation can prevent disease progression and guide timely therapy. This balanced approach emphasizes that there is a spectrum of presentation, ranging from subtle, chronic signs to acute, urgent phenomena, and that appropriate action depends on the trajectory of symptoms and the overall clinical picture. Remember that liver health is a dynamic facet of wellness that benefits from ongoing attention and proactive care rather than a reactive response to a single incident.

How to approach conversations with healthcare providers

Approaching a medical visit with clarity and calm helps ensure that important information is conveyed effectively. Start by outlining your concerns, describing when symptoms began, how they have evolved, and any associated factors such as meals, activity levels, or changes in medications. Prepare a concise timeline of symptoms, including any episodes of jaundice, itching, changes in digestion, or unintentional weight variations. List all medications, vitamins, and supplements you take, including dosages and frequency, as certain substances can influence liver function or interact with treatments. Discuss lifestyle factors in a nonjudgmental manner, including alcohol use, dietary patterns, sleep quality, and stress, because these factors influence liver health and can inform recommended changes. Bring past medical history, family history of liver disease, and any prior test results to provide context for the clinician. If a referral to a hepatologist or specialist is appropriate, ask about the rationale and what tests might be expected. Always inquire about what the results mean, what follow-up is needed, and how to monitor health going forward. This collaborative mindset supports patient empowerment and helps ensure that decisions about testing, treatment, and lifestyle adjustments reflect personal preferences and medical evidence. Clear communication also reduces the likelihood of misinterpretation and fosters a shared plan focused on preserving liver health and improving overall well-being.

When discussing risks and options with a healthcare team, it is reasonable to request noninvasive assessments first when appropriate. For example, elastography or specialized imaging can provide valuable information about liver stiffness and fat content without requiring a biopsy in many cases. Understanding test alternatives encourages patient engagement and can alleviate concerns about invasive procedures. If biopsy becomes necessary, clinicians typically explain the purpose, benefits, potential risks, and what to expect during recovery, helping patients make informed decisions. The overarching goal is to establish a partnership with clinicians that centers on education, respect for patient values, and transparent communication about uncertainty and prognosis. By cultivating this collaborative approach, patients feel more confident in the diagnostic process and more capable of participating actively in their care plan.

In addition to direct clinical conversations, patients can benefit from credible educational resources about liver health. Seeking information from reputable sources supports informed decision-making and helps people ask more precise questions during visits. However, it is important to distinguish between general information and individualized medical advice. Each person’s liver health is shaped by a unique combination of factors, including genetics, lifestyle, coexisting conditions, and current treatments. Therefore, while knowledge is empowering, it does not replace professional evaluation. With thoughtful preparation, ongoing dialogue with clinicians, and adherence to recommended follow-up, individuals can navigate the complexities of liver health while maintaining a sense of control and resilience. This collaborative process aims to reduce fear, promote proactive care, and keep liver health at the forefront of long-term wellness planning.

Ultimately, recognizing early signs of liver disease requires attention to a constellation of symptoms, risk factors, and objective test results. It invites a proactive stance that values preventive care, timely evaluation, and personalized management. By staying attuned to bodily signals, maintaining healthy lifestyle choices, and engaging openly with healthcare professionals, individuals position themselves to preserve liver function, minimize complications, and enjoy a higher quality of life. This perspective emphasizes that early recognition is not an endpoint but a gateway to meaningful care, enabling people to take informed steps toward health, resilience, and well-being.

In the broader context of public health, raising awareness about early liver disease signs can encourage communities to engage in preventive measures, seek screening when appropriate, and support one another in making healthy choices. Health education efforts that clearly explain risk factors, signs, and available testing can reduce delays in diagnosis and promote timely interventions. Dialogues about liver health with family, friends, and colleagues help normalize conversations about a topic that affects millions globally. The cumulative effect of individual vigilance translates into stronger health outcomes at a population level as more people gain access to early, accurate assessment and appropriate care. By fostering a culture of curiosity, care, and action around liver health, society as a whole advances toward reduced burden of liver disease and improved well-being for all.