Kidney stones are hard mineral crystals that form in the urine within the kidneys. They can begin quietly without obvious symptoms and then progress to cause a range of signs that may hint at their presence. Detecting these signals early matters because timely evaluation can prevent complications such as infection or blockage, and it can guide simple, conservative management before more invasive approaches become necessary. The journey from subtle signals to a clear diagnosis often involves paying careful attention to changes in urine, discomfort patterns, and overall well being. This article explores the spectrum of early signs, how they manifest, what tests doctors use to confirm stones, and how to respond appropriately to protect kidney health over time.

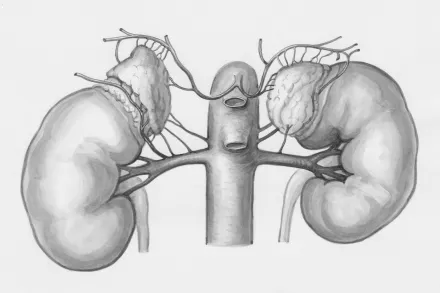

What kidney stones are and why early detection matters

Kidney stones are crystalline mineral deposits that form when the urine becomes overly concentrated with minerals such as calcium, oxalate, or uric acid. When these minerals stick together, they can create hard masses that may remain in the kidney or travel down the urinary tract. The earliest signs of stone formation can be subtle because a small stone may pass without causing dramatic pain. However, even tiny stones can irritate the urinary tract lining or intermittently obstruct flow, which can produce signals that should not be ignored. Early detection serves two critical purposes: it helps prevent a stone from growing larger or causing a blockage, and it allows clinicians to identify underlying metabolic issues that contribute to stone formation so that preventive measures can be tailored to the patient. Recognizing early signs also minimizes the risk that a stone will become a medical emergency requiring urgent intervention. In most cases, the sequence of events begins with minor urinary changes or mild discomfort that, over hours to days, evolves into more noticeable symptoms if the stone moves or enlarges.

Common early signs you might notice

Many stones start with signs that are easy to overlook or attribute to a transient illness or dehydration. A person may notice a slight change in urine color, such as pink or reddish tinge, which reflects the presence of blood from irritation within the urinary tract. Blood in the urine can be intermittent, especially with small stones that move in and out of the tract. Alongside color changes, a sense of urgency to urinate or a frequent urge to empty the bladder can appear even when the urine volume is not large. In some cases, you may notice a burning sensation during urination that is not explained by a simple urinary tract infection. These early signals can be accompanied by mild cramping or a sense that something is off in the lower abdomen or back. It is important to understand that these symptoms do not automatically confirm a stone, but they should prompt a careful check with a healthcare professional, especially if they persist or recur. Clarifying these signs early allows clinicians to rule out other conditions and to determine whether imaging or lab testing is warranted to look for stones or related abnormalities. Since hydration status can influence both symptoms and test results, tracking how signs change with fluids can also provide useful information to a clinician assessing your risk.

Pain patterns and urinary symptoms

The most characteristic sign of a stone moving into the urinary tract is flank pain that comes in waves and may intensify toward the groin. The pain often starts in the flank or side, below the ribs, and travels downward as the stone shifts position. It can be accompanied by restlessness and an inability to find a comfortable position. Some people describe the pain as a sharp, stabbing sensation, while others feel a dull ache that persists for hours. Alongside pain, there may be blood in the urine, which can appear pink, red, or brown. The presence of blood signifies irritation of the lining of the urinary tract and warrants medical evaluation. Urinary symptoms frequently accompany stone passage: a persistent urge to urinate, increased frequency, or a burning sensation when urinating. Some stones are very small and pass quietly with only minimal discomfort, while larger stones can cause intense waves of pain that require medical assessment. If pain is concentrated in the lower abdomen or groin and accompanied by fever or vomiting, it should be treated as a sign of potential complication that needs prompt care. Recognizing these pain patterns helps differentiate a stone episode from other common causes of abdominal or back pain and guides timely testing.

Nonpain signs that may appear early

In addition to pain, kidney stones may produce subtle signs such as nausea, vomiting, or a general feeling of being unwell. Some individuals report dizziness or lightheadedness during a flare, especially if hydration is poor. The skin may feel cool and sweaty during a painful episode. A fever or chills is not common with uncomplicated stones and usually indicates a concurrent infection, which requires urgent care. If fever accompanies pain, seek emergency evaluation because infection can be dangerous. Some people notice that their urine is cloudy or has a strong, unusual odor, which may reflect infection or concentrated urine from dehydration. Recognizing these early nonpain signals can help you decide when to pursue testing rather than waiting for a dramatic episode to occur. While these signs do not guarantee a stone, they help build a picture that warrants medical assessment, particularly when combined with ongoing changes in urinary habits or hydration status.

What tests help confirm kidney stones and locate them

Medical evaluation begins with a careful history and physical exam, followed by urine tests to look for blood, infection, or crystals. A urinalysis can detect microscopic blood and signs of infection. A blood test may measure levels of calcium, uric acid, and kidney function in order to identify metabolic contributors to stone formation and to assess how well the kidneys are working. Imaging studies are crucial for confirming the presence, size, and location of stones. A noncontrast computed tomography scan (CT) is highly sensitive and specific for stones and can reveal stones that are invisible on standard X-rays. An ultrasound is a radiation-free alternative that is particularly useful in pregnant patients and children, or when radiation exposure should be minimized. Some stones are visible on plain X-ray images if they contain certain minerals, but not all stones are radiopaque. The choice of imaging depends on age, pregnancy status, body habitus, and the clinical scenario, including the severity of symptoms and the likelihood of obstruction. Interpreting the results requires a clinician, because symptoms may arise from other conditions such as urinary tract infections or muscle strain, and the management plan depends on stone size and location as well as the presence of any complications.

When to seek urgent medical care

There are specific red flags that should prompt immediate medical attention. Sudden, severe, persistent pain that does not improve with basic measures, or pain accompanied by fever, chills, or fainting, requires urgent evaluation. Inability to keep fluids down, signs of dehydration, or a stone causing an inability to pass urine should also prompt prompt care. Any suspicion of infection requiring rapid treatment is an emergency. For pregnant individuals, fever or severe flank pain calls for urgent obstetric and urologic assessment because both the pregnancy and the kidney stone need careful monitoring. If you experience a new onset of back or flank pain combined with fever or vomiting, consider seeking care promptly to be sure there isn’t an infection or another condition that needs treatment.

Who is more likely to develop stones and what early signs may differ

Kidney stones affect people of various ages but are more common in adults between the ages of twenty and fifty. Men historically experienced stones more often than women, although the gap has narrowed with changes in diet and lifestyle. A prior history of stones increases the likelihood of recurrence, so individuals with past episodes should be especially vigilant for early signals such as a sudden urge to urinate or mild flank discomfort that accompanies meals high in salt or animal protein. People with certain medical conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, hyperparathyroidism, or metabolic disorders, may have a different pattern of symptoms or a different rate of stone passage. The appearance of blood in the urine may be episodic and not continuous, and in some cases the only early sign is a minor change in urine color that becomes more pronounced with hydration status. In older adults, symptoms can be subtler and may be mistaken for a back strain or urinary tract infection, so objective tests become essential when symptoms persist beyond a day or two.

Simple explanations of how stones form and why early signs emerge

Understanding the process of stone formation helps in recognizing early signs. Stones form when minerals such as calcium, oxalate, uric acid, and citrate crystallize in urine due to imbalances in concentration or pH. A consistently low urine volume allows minerals to concentrate, increasing the risk that they will precipitate out of solution and begin to stick to the kidney lining. When stones begin to move, they irritate the urinary tract lining and provoke the sensory nerves that signal pain. In the earliest stages, this irritation may be mild and intermittent, resulting in a gradual increase in awareness of bodily sensations rather than a sudden explosion of pain. Many small stones travel from the kidney into the ureter, the tube that drains the kidney to the bladder, and cause episodic pain as they travel. The precise in-between signals are influenced by the stone’s size, shape, and where it is in the tract. As a result, early signs can be varied and may include both urinary changes and mild inflammation of the urinary tract lining. Recognizing this progression can help patients understand when to seek medical testing rather than relying solely on sensation.

How doctors use your early signs to decide on tests and management

Clinicians combine the reported signs with physical examination and risk factors to decide which tests to order. If the symptoms strongly suggest obstruction or infection, imaging is prioritized. If the signs are mild and there is no fever, a slower workup may be arranged with follow-up. The rate of progression matters; in some patients, stones remain tiny and pass on their own with proper hydration, while others grow larger and require procedures. The ability to detect early signs allows clinicians to choose conservative therapy such as hydration and pain control while postponing invasive interventions until they are clearly needed. Tracking the evolution of symptoms over hours to days is often part of the evaluation process, because stones can pass quickly or become stuck, depending on their size and location. The patient’s history of stone composition, diet, and hydration habits helps shape the prevention strategies to follow after the initial episode.

What you can do at home when you suspect a stone is passing

Home management focuses on staying well hydrated to promote urine flow and reduce the risk of concentrating minerals again. Drinking water steadily throughout the day helps maintain urine output and can support spontaneous stone passage for small stones. It is important to avoid dehydration, because dehydration concentrates all urinary minerals and can worsen symptoms. If pain is manageable, over-the-counter analgesics such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may relieve discomfort, but you should consult a clinician if the pain is severe or persistent. Some individuals find relief by applying heat to the abdomen or side to comfort the muscles that spasm around the stone. A home diary of symptoms, urine color, and fluid intake can assist clinicians in understanding whether a stone is progressing or if a red flag like fever has appeared. You should not attempt to crush or break stones at home; this requires professional care. If you notice blood in the urine that persists or if you experience new fever or vomiting, contact your healthcare provider promptly, because these changes can indicate complications that require evaluation in a clinic or emergency department.

Dietary and lifestyle factors that influence early signs and stone formation

Dietary patterns influence the likelihood of stone recurrence and the appearance of early signs. A diet high in salt increases calcium excretion in urine, which can promote stone formation. Excessive animal protein intake may raise calcium and uric acid levels and reduce citrate, a natural stone inhibitor in urine. Citrate helps prevent crystallization, so including citrus fruits or citrate-containing beverages might be beneficial under medical guidance. Calcium-rich foods are important for overall bone health, but excessive calcium supplementation without medical supervision can also contribute to stone risk in some individuals. A balanced intake of fluids, fiber, and plant-based foods can promote a healthier urinary environment. Some people benefit from limiting high-oxalate foods in cases where oxalate stones are predominant, especially in people with a known propensity toward oxalate stone formation. It is essential to tailor dietary changes to each person’s metabolic profile and medical history, so you should discuss any major diet plan with a clinician or a registered dietitian who understands kidney stone prevention. In addition to diet, lifestyle changes such as regular physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, and avoiding dehydration during hot weather or intense exercise can reduce the risk of stone formation. Following medical advice about hydration targets and dietary adjustments helps ensure that early signs do not escalate into more painful episodes.

What happens after detecting stones: short-term and long-term steps

Once stones are detected, doctors assess whether intervention is needed immediately or whether watchful waiting is reasonable. In many cases, small stones can pass on their own with supportive care, including hydration and pain relief, while larger stones may require procedures such as lithotripsy or endoscopic removal. In the short term, managing pain effectively, preventing dehydration, and monitoring for infections are priorities. In the longer term, addressing underlying causes such as hypercalciuria, hyperoxaluria, or uric acid overproduction becomes part of a comprehensive prevention plan. Medical teams may recommend tests to identify metabolic abnormalities that contribute to stone formation and to tailor prevention strategies for each patient. Education on recognizing early warning signs and when to seek care helps reduce delays in treatment and improves outcomes. Ongoing follow-up ensures that any recurrent stones are detected early and that preventive measures are adjusted as needed.

Is there a role for screening in people without symptoms?

Screening in asymptomatic individuals is not routinely recommended because most stones do not cause pain or harm until they become large or cause obstruction. However, certain high-risk populations, such as those with a strong family history, specific metabolic disorders, or prior repeated stones, may benefit from periodic screening and metabolic evaluation to catch risk factors before symptoms appear. In these cases, clinicians may monitor urine parameters, blood tests, and dietary habits over time as part of a preventive strategy. Regular medical follow-up for populations at high risk can help identify subtle changes that precede stone formation, though such screening must be balanced against potential costs and anxiety. The aim of early detection in these contexts is to prevent severe episodes by recognizing trends rather than relying on dramatic pain events, and it is always guided by a clinician who knows the patient’s medical history and risk profile.

How to distinguish kidney stones from other conditions with similar early signs

Several conditions can mimic some signs of kidney stones, including urinary tract infections, muscle strains, or gastrointestinal issues that cause abdominal pain. The sudden colicky flank pain of a stone is distinctive, but similar pain can occur with kidney or urinary tract infections, appendicitis, gallstones, or pancreatitis. Blood in the urine can arise from different urinary tract conditions, not only stones. Because symptoms may overlap, a careful evaluation with urinalysis, imaging when appropriate, and a physical exam is essential to ensure the correct diagnosis. Patients should report the onset, location, timing, and running history of symptoms, including whether pain radiates to the groin, as well as any associated fever, vomiting, or urinary changes. This information helps clinicians decide whether stones are the culprit or if another condition is responsible, and it guides the selection of tests and the treatment plan.

Empowering yourself with knowledge: how to keep yourself safe

Being aware of early signs enables you to seek care promptly and to participate actively in your health care decisions. If you notice any of the typical signs discussed above, especially if they occur in combination with dehydration or fever, you should contact a clinician or visit an urgent care center. Keeping a simple diary of symptoms, fluid intake, and urine color can be a powerful tool in conversations with your doctor. Educating family members about the potential signs can also help provide support during episodes. People who have had stones in the past may be more alert to subtle changes that previously went unnoticed, and this awareness can prevent delays in treatment. When possible, carrying medical information about past kidney stone episodes, known stone types, and current medications can help clinicians tailor a fast and effective assessment strategy.

Bottom line: remember the syndromic clues and act early

In summary, early signs of kidney stones appear in a spectrum from subtle urinary changes to distinctive pain patterns. Recognizing the combination of flank or groin pain with or without blood in the urine, along with symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or fever, should prompt timely medical evaluation. The path to confirmation relies on a mixture of urine testing and imaging, while treatment plans depend on stone size, location, and whether infection or obstruction is present. By staying hydrated, monitoring symptoms, and seeking professional guidance when signals appear, you increase the likelihood of managing kidney stones effectively and reducing the risk of complications. Early awareness also supports prevention by allowing clinicians to identify metabolic contributors and recommend targeted strategies to reduce recurrence. This approach makes it possible to manage symptoms with comfort and safety while preserving kidney function over the long term.